BY DAFYDD MOORE

James Macpherson’s Poems of Ossian (1761-3) present themselves as the poetic remains of the third-century Celtic prince and bard Ossian (in fact they were inspired, as we might say, by the Gaelic heroic verse Macpherson collected in the Highlands of Scotland but were for the most part more down to him than any identifiable source).

They were one of the publishing sensations of the late eighteenth century, and not only for the controversy they generated. Ossian was Napoleon’s favourite poet, the latter’s enthusiasm extending to Ossian-inspired interior design.

The poems take the form of the reminiscences of Ossian in old age, as he recounts the deeds of his youth in the court of his father, the mighty Fingal. Ossian is a living ghost, a man who has outlasted his time, his friends, his family, his culture. Written less than twenty years after the last great independent political act of Scottish Gaeldom – the Jacobite Rising of 1745-6 – the poems are frequently read as a lament for the passing of a heroic Celtic world:

Often have I fought, and often won in battles of the spear. But blind, and tearful, and forlorn I now walk with little men. O Fingal with thy race of battle I now behold thee not. The wild roes feed upon the green tomb of the mighty king of Morven.— Blest by thy soul, thou king of swords, thou most renowned on the hills of Cona!

In the same way, Ossian’s knowledge of that which is no more leads to a profound sense of future decline and the mutability of all things, that ‘they have but fallen before us: for, one day, we must fall’.

Yet for all its apparently archaic language and subject matter (redolent of the King James Bible) and its lament for a lost past, Ossian is also a very modern text. It proved a seminally important work for British Romantic Literature. While the tradition of meditation on the passing of all things stretches back into the ancient world, the forms of nostalgia and regret expressed within Ossian are essentially modern.

Ossian is both haunted and nourished by his past; he is torn between wanting to remember and wanting to forget. For every memory that reminds him of happier times, there is one that tortures him with the bitter knowledge of all that he has lost; of, in the words of Wordsworth (evoking Ossian) some 40 years later, ‘what has been | And never more shall be’.

This modernity also extends to its interest in a range of the ideas characteristic of the Scottish Enlightenment. Macpherson knew many of the thinkers of the period, including David Hume, Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson as well as others now forgotten but who were equally as influential in their day. It has long been accepted that some of the Scottish Enlightenment’s key ideas find their way into Ossian.

One tiny but interesting (and I think previously overlooked) example comes in a well-known passage known as Ossian’s Address to the Sun:

But thou thyself movest alone; who can be a companion of thy course! The oaks of the mountains fall: the mountains themselves decay with years; the ocean shrinks and grows again [my emphasis]

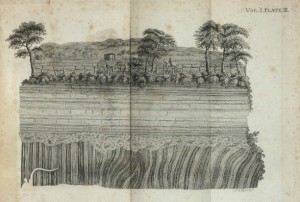

Macpherson footnotes this with references to Milton’s Paradise Lost and Virgil’s Aeneid, but it is the phrase in italics that interests me here. The first half seems self-evident enough to us, but in 1761 it offers a novel and potentially controversial commitment (because it questions Biblical understandings of the formation of the Earth) to an idea that we would today recognise as the geomorphological process of denudation (or erosion).

Similarly, while in isolation the comment about the ocean might be taken to refer to the rhythm of the tides, its juxtaposition with the idea of the erosion of mountains suggests it too could have a geomorphological reference to the related issue of historical changes in sea level.

I am not aware of any evidence that Macpherson knew the most famous Scottish Enlightenment proponent of such ideas (and his almost exact contemporary) James Hutton, though it is likely that Hutton knew Ossian if only because the poems were so hard to avoid in the two generations following its publication. In fact, Hutton and Macpherson mixed in the same Edinburgh intellectual circle albeit several years apart (Macpherson at the start and Hutton from the end of the 1760s), and they certainly had a number of mutual friends.

Given that, Ossian’s rather matter of fact encapsulation of two elements of Hutton’s thinking (first made public in 1785 and then more famously as his Theory of the Earth in 1788) – put crudely, not only that landscapes change but, even more crucially, that it takes a long time for them to do so – is eye-catching.

Literary critics can get over excited at such moments, and more research would be needed before one could say anything too definitive. But it is an example of the importance of placing a close reading and attention to the details of literature within other disciplinary contexts.

An oft-remarked feature of Ossian is that it is both familiar and, at the same time, slightly out of kilter (what, after Freud, we might call uncanny). There are plentiful examples in terms of language, style, description and ideas, but this would not strike a modern reader as being one of them. Yet to appreciate how weird this notion would have been to many in the 1760s is to recover another example of Ossian’s familiar strangeness.

Equally it is worth pondering what further investigation of the history of this idea during the period might reveal. But for now, suffice it to say that Macpherson’s literary and Hutton’s geological evocations of ‘deep time’, of the mutability of all things, and of the profound links between the past, the present and future, can be seen as part of a shared cultural discourse whose impact was felt across disciplines we think of today as very separate.

I am grateful to Professor Iain Stewart, Director of the Sustainable Earth Institute at Plymouth University, for confirming my understanding of matters Huttonian. Any mistakes or misunderstandings remain, however, my own.

About the author:

About the author:

Dafydd Moore is Professor of Eighteenth-Century Literature at Plymouth University, Executive Dean of its Faculty of Arts and Humanities and interim Pro-Vice Chancellor Research. He is widely published on Macpherson and Ossian, including Enlightenment and Romance in the Poems of Ossian (2003) and Ossian and Ossianism (4 volumes, 2004). His edited collection, The International Companion to James Macpherson and Ossian will appear later in 2016.