BY ROBERTA MOCK

While so many of us mourn and remember Prince, who died on 21 April, the global media drips the details of his final days, expressing our collective surprise that his death appears to have been due to an overdose, the consequence of long term addiction to prescription painkillers.

Over and over we read about how “clean” Prince appeared to be: he didn’t eat meat; he didn’t drink alcohol; nobody ever saw him take drugs. And this is intimately related to why we are shocked by the fact that the man who was so present, so live in the moment, is no longer here.

Despite Prince’s legendary unknowability, we find it hard to believe that a “dirty” – or perhaps, more appropriately, a “toxic” body – could somehow hide its “true” nature. This, I think, is based on the assumption that what would need to be (impossibly) concealed is detachment or a sense of absence.

And this all leads me to reflect on the complex web that connects the ways in which toxicity is and has been performed (willingly or unwillingly), the limits and limitations of the performing body, and the expectations of audiences.

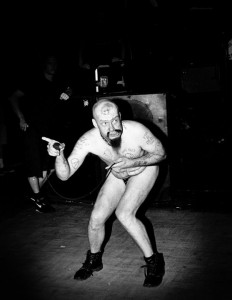

In many ways, G.G. Allin can be considered the opposite end of the spectrum to Prince in that his toxic body was always made explicit – indeed, it was his calling card. Allin, whose parents apparently did formally name him Jesus Christ at birth, performed aggressive, often misogynistic, punk and sometimes country rock. Remembered now largely for his near mythical abject extremity, he often said that he was going to commit suicide on stage and take the audience with him.

The night he died in 1993, so the story goes, Allin had taken a shed load of drugs before going on stage. When the show was stopped abruptly, he smashed up the place, before marching through the streets of New York, naked and covered in shit, followed by his acolytes creating mayhem. They eventually settled into a party in the flat inhabited by someone called Johnny Puke.

At some point during the night, Allin died of a heroin overdose but nobody noticed. They just thought he was fucked up – people took photos with him, not realizing he was dead. Nor, when enough people sobered up, could everybody believe that this messianic namesake wouldn’t resurrect, as he seemed to have done many times in the past.

The line between life and death was pretty thin at his wake too. Photos were taken with his unwashed body; drugs were placed in his mouth and swilled down with Jim Beam.

I am only being semi ironic when I say that G.G. Allin had what we might call “presence”, even – or perhaps especially – when the line between life and death was difficult to distinguish. According to Erica Fisher-Lichte, presence is a process of consciousness (again, I acknowledge a certain contradiction here) articulated through the body and sensed by the spectators through their bodies.

It is perhaps no coincidence that, in the vocabulary of 1960s ecstatic performance (especially the Artaudian branch), presence was often placed in direct contrast to spectacle – which rather than unifying and celebratory, is managed to support hegemonic ideologies through distancing effects.

Like Richard Schechner before her, Fisher-Lichte links presence to ecstasy and presentness. “It can be assumed,” she writes, “that the performer’s ability to generate presence is based on his mastery of certain techniques and practices to which the spectators respond.” For G.G. Allin’s fans, what he mastered was the ability to take near lethal – or as the case may be, at least once, lethal – cocktails of drugs and lead them into scenarios of the released repressed. His were quasi-shamanistic practices of the toxic body.

Alas, those were simpler times. According to Teena Gabrielson, although “once identified with the deviant, the venomous, [and] the profane, we are all toxic now”.

As a very basic indicator, she cites a 2006 study of newborn babies in the United States which found that they had absorbed, on average, 200 industrial chemicals and pollutants into their bodies through their mothers’ wombs. Gabrielson calls this phenomenon “the normalized toxic body”, which “obscures the inside from outside, the subject from environment, the private from public, the natural from artificial.”

But we don’t expect our performers to be normal, especially our celebrity performers. Our vicarious bond with them results in at least two different sets of extra-ordinary bodily techniques. In one, celebrity performers actively and seemingly effortlessly work to have bodies that are far less toxic than our own.

In another, they make their bodies supertoxic and we ogle at the extent to which they can push the limits of morbidity. Jokes circulated for decades about whether Keith Richards was actually still alive, whether it was a reanimated cadaver with freshly transfused blood who was actually onstage with the Rolling Stones.

When Whitney Houston died in February 2012, toxicology tests showed she had cocaine, benedryl, flexiril, marijuana, and xanax in her system. The cause of death, according to the coroner, was “accidental drowning” in the hotel bathtub.

Houston didn’t die because she took too much of any one thing. She died of the accumulated effect of her supertoxicity – just like Amy Winehouse whose tiny body just finally seemed too saturated to carry on functioning.

And frankly, we – or at least our other proxies, the tabloid media – were there waiting, watching, lovehating the show. A minor industry developed around pap photos of Amy scratched, bleeding, dishevelled, nostrils caked, fighting, blurry. How many google searches had been done in the years before her death on “Whitney Houston + no teeth”?

These were spectacles of consumption managed for public consumption. As Mary Russo has pointed out, becoming a spectacle is particularly problematic for women in the way that it implies not only a loss of boundaries but also inadvertency.

Whitney knew what was expected of a mainstream superstar. She kept her addictions private for as long as possible, denying them, telling Oprah that “crack is whack” and then confessing, producing her own guilt, apologising and doing penance when her body finally betrayed its toxicity in public.

But Amy, like Charlie Sheen, refused to play that game. In a 2007 interview published posthumously in Q, Winehouse said “You can see people that do coke are quite alert. I don’t wanna be alert. I want to be out of my fucking nut, d’you know what I mean?”

Clearly she was referring to people who only take cocaine. A few months later she was hospitalized after taking a cocktail that seemed as ludicrously cartoon as her ever increasing beehive – heroin, cocaine, ketamine, ecstasy and, Amy’s particularly favourite poison, alcohol.

At the Brit Awards that year, Russell Brand joked that Winehouse’s “surname’s beginning to sound like a description of her liver.” And yet, after her death, it was Brand who eulogised on his website: “Addiction is a serious disease; it will end with jail, mental institutions or death. All we can do is adapt the way we view this condition, not as a crime or a romantic affectation but as a disease that will kill.”

As both a celebrity and a self-identified smackhead-in-remission, Brand understood the tightrope Winehouse was walking professionally. Her body was at the centre of two different types of performance – one, the quotidian freakshow and one, as a serious musician within a globalized culture industry. That the two were not permitted to coalesce on stage was made most evident during one of Winehouse’s final performances, the first date of an aborted European tour in June 2011 in Belgrade.

Onstage she seemed drunk and confused, staggering and slurring. The audience booed unsympathetically. “I still love you,” she told them. Videos quickly began circulating on youtube. The Serbian defence minister said the show was “a huge shame and a disappointment. She is far from being a queen. She’s more like a patient of a rehabilitation clinic for drugs and an alcohol addict.”

Now, you could say – and many did – that this was a naïve response, given Winehouse’s erratic performance history over the previous few years and the fact that she had burst into public consciousness when her voice reached deep down into our bodies to inform us uncategorically that she wasn’t going to go to rehab, no no no.

So I am going to offer another possibility: not that Winehouse offended through and as a toxic body, but that this body no longer cared about being, communicating and making meaning with her audience. Allin may have been dead, but he was present. Amy was live but she was absent and that was something her fans could or would not forgive in the moment.

About the author:

About the author:

Roberta Mock is Professor of Performance Studies and Director of the Graduate School at Plymouth University.