Sourced : Real Clear Defense

By Eric S. Edelman (Senior Advisor at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey, as well as former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy)

The modern Republic of Turkey remains one of the “pivotal” states in the international system. The country’s role as a U.S. treaty ally sitting astride the division between Europe and the Middle East, as a Black Sea littoral state bordering on a revanchist Russia, and an important energy hub ensures that it will remain a crucial player. Since the 9/11 attacks, the U.S.-Turkish relationship has been on a rollercoaster ride of highs and lows.

While bumpy patches have been more the norm lately, there have been eras of warm ties. The EU decision to open accession talks with Turkey in December 2004 – a longtime objective of U.S. national security policy since the 1960s – stands out in that regard (and it is no coincidence that U.S. standing among the Turkish public, as measured in the Pew Charitable Trust’s poll, was at its highest then).

More often than not, however, the relationship has been marked by serious differences over the political future of Iraq (and the best way to deal with the PKK challenge to Turkey emanating from the Kurdish north), how to deal with a nuclearizing Iran, and most acutely, the roiling conflict in Syria and the rise of the Islamic State (IS). It is an unfortunate fact that on occasion these differences have given rise to outbursts of popular anti-Americanism in the often febrile Turkish media.

Even before 9/11, the rise of the Islamist-oriented Justice and Development Party (AKP), and the convulsions that followed in the Middle East, the U.S.-Turkish relationship had been marked by ups and downs. The one steady element in the relationship always appeared to be the military-to-military ties that bound the two countries together.

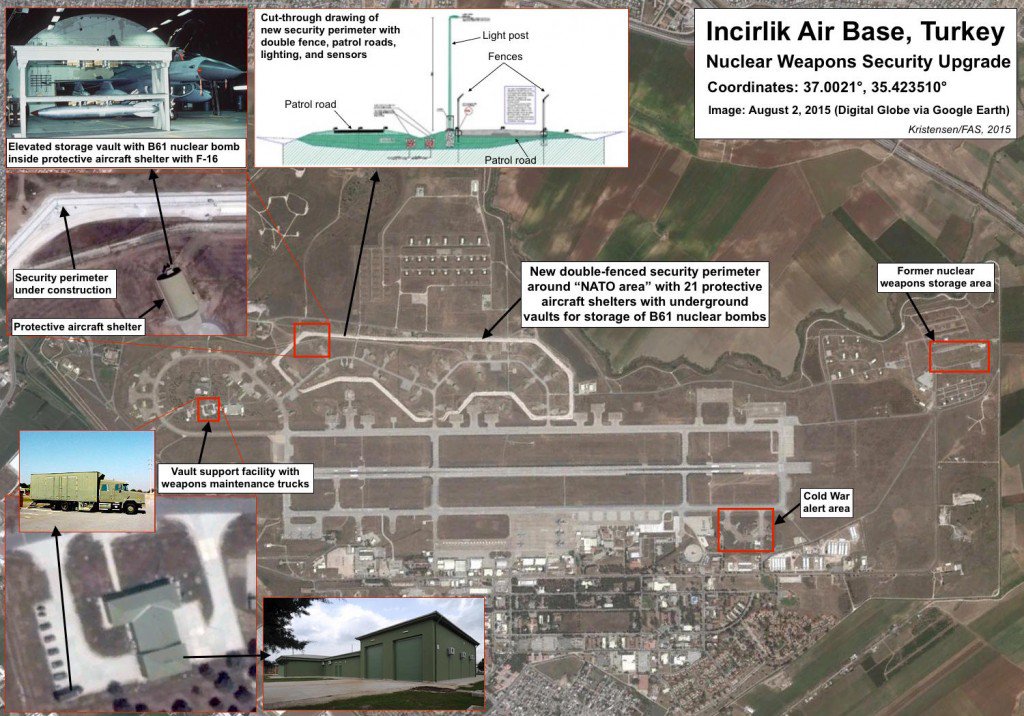

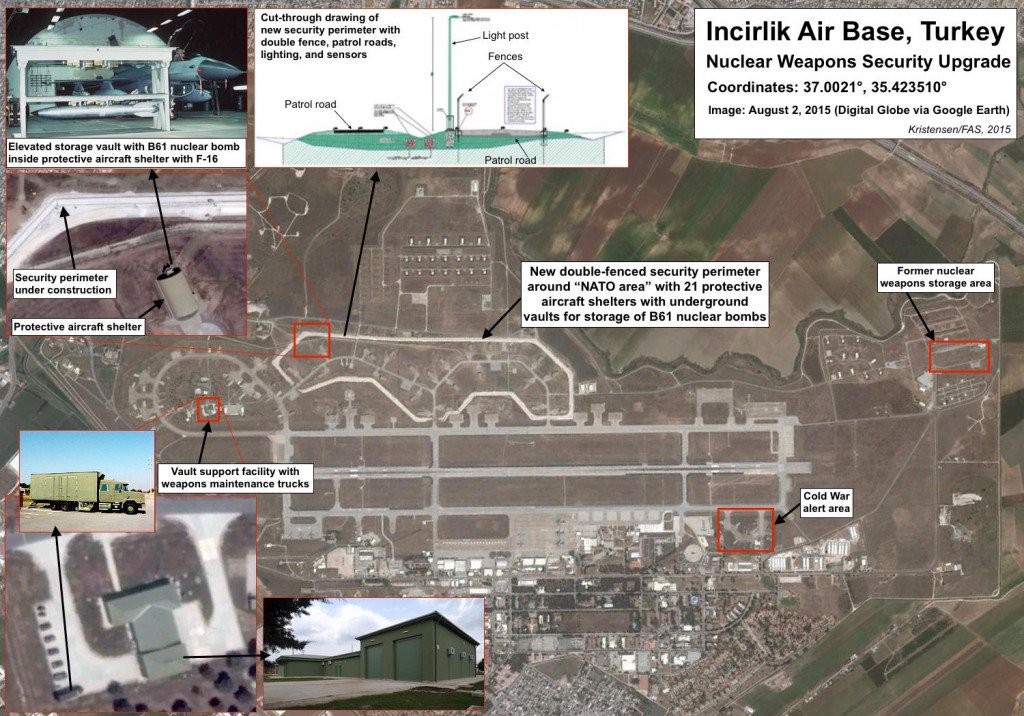

Turkey had the second largest military establishment in NATO, one of the largest International Military Education and Training (IMET) programs in the world, and important bases near the Soviet Union that made it an important military partner for the United States during the Cold War. In particular, for over 70 years, the Incirlik Air Base near Adana in southeastern Turkey played a vital role in U.S. military planning and in maintaining the “northern tier” strategy of blocking Soviet access to the eastern Mediterranean and Persian Gulf.

When the Cold War ended, some analysts questioned the continuing utility of Incirlik and the ongoing U.S. presence, but the fist Gulf War quickly brought that debate to an end. President Turgut Ozal’s courageous decision, overruling his then chief of defense, to join the U.S.-led coalition to reverse Saddam Hussein’s aggression against Kuwait ushered in an era of very close U.S.- Turkish collaboration.

By the end of the decade, President Bill Clinton proclaimed a U.S.-Turkish “strategic partnership” in his speech to the Turkish Grand National Assembly. Today, in the wake of the failed coup attempt of July 15, 2016, those words seem increasingly hollow.

Even before the botched effort by elements of the military to overthrow the AKP government, Turkey was on a domestic trajectory marked by increasing authoritarianism and troubling government relationships with dangerous Islamist groups.

In the wake of the coup, a rising tide of officially sanctioned and, in some cases, government-instigated anti-Americanism, coupled with the hollowing out of the Turkish military and continuing terrorist attacks by both Kurdish and Islamist extremists, have once again raised the question of the future utility of America’s continued presence at Incirlik.

Although I join most observers in continuing to believe that the U.S.-Turkish relationship is crucial and that Incirlik’s role is particularly important in the context of the anti-IS struggle, it is clearly time to face the possibility that the U.S. may, against its will, be forced to leave. Ths would be a serious discontinuity in the NATO alliance and the U.S.-Turkish relationship, and it ought not to be approached in a “fit of absence of mind.”

Ths meticulous Foundation for Defense of Democracies study provides the broader context for considering the prospects for Incirlik’s future. It not only charts the history of the base’s role and our military-to-military ties, but it lays out the serious issues that would follow from a U.S. exit and it also canvasses the alternatives.

The best outcome would clearly be for the U.S. to remain in Incirlik for reasons that include the effectiveness of the campaign against IS and the ongoing need for U.S. extended nuclear deterrence in Europe. Yet, suggesting that the U.S. has alternatives may serve an important purpose. It can help Turkish officials recognize the importance of the U.S. connection to Turkey. It might even help preserve it.