Sourced : Defence One

By Joe Cirincione & Tytti Erästö

The one constant in Donald Trump’s foreign-policy views has been his desire to improve relations with Moscow. “There’s nothing I can think of that I’d rather do than have Russia friendly, as opposed to the way they are right now,” he said in July, a theme he has since reprised in various ways.

It is no secret that Russian President Vladimir Putin favored Trump in the election. But a Putin-Trump bromance and shared business interests can only take this so far. To transform relations, Trump will have to address Russia’s deep concerns about U.S. missile defense in Europe.

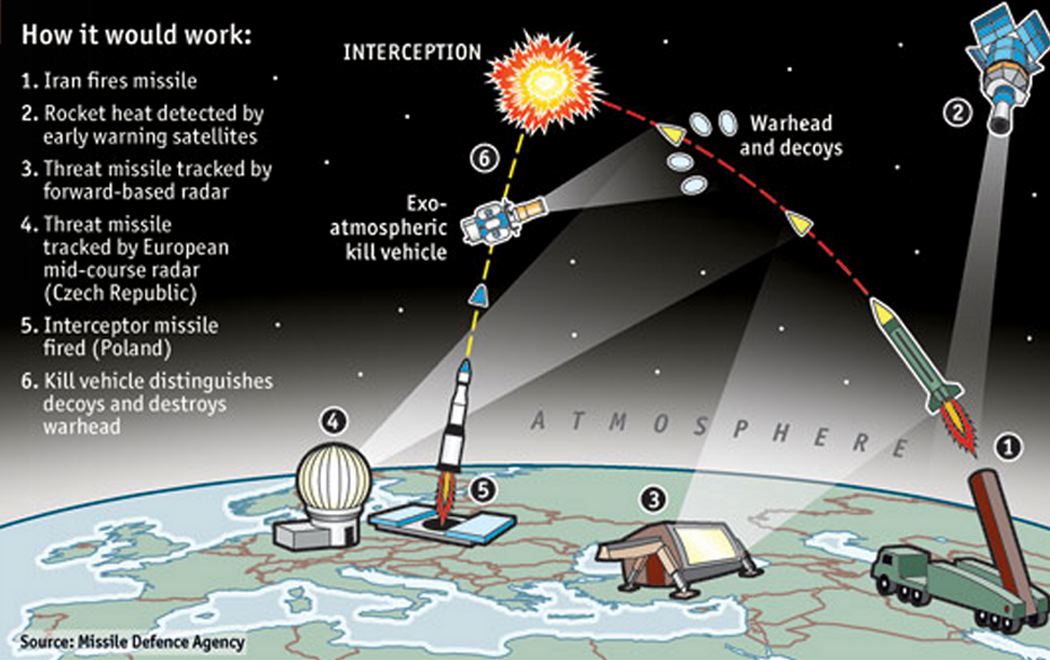

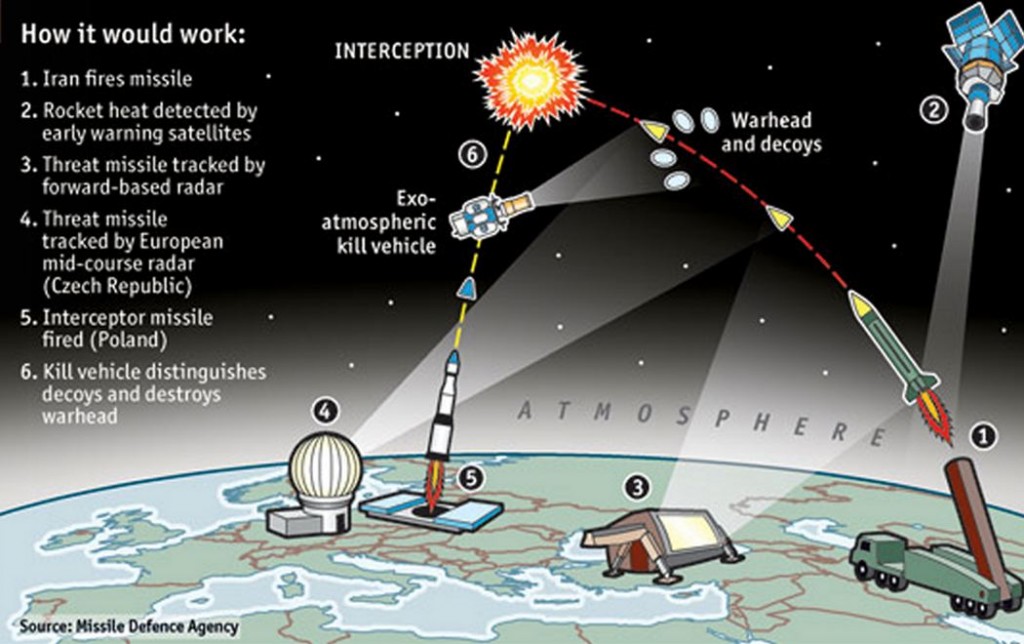

Missile defenses are weapons whose purpose is to destroy enemy missiles before they reach their target. Some of the systems designed to shoot down short-range weapons, such as Scuds, work well in tests. But despite hundreds of billions of dollars spent on various long-range interceptor concepts over the past 30 years, the U.S. has little to show for the effort.

The existing systems are widely considered ineffective. However, future technological development might theoretically make missile interceptors more reliable. For Russia’s leaders, this is a scary prospect. They fear effective defenses could undermine their country’s nuclear deterrent, making it vulnerable to a U.S. first strike.

Russia is particularly irked by the U.S.-NATO missile defense project in Europe. Moscow has long called for legal guarantees that the system not be directed against Russia, to no avail. Its frustration has grown in recent years. As Putin said in May, “Nobody listens to us…we do not hear anything but platitudes, and those platitudes mainly boil down to the fact that this is not directed against Russia…Let me remind you that initially there was talk about thwarting a threat from Iran…Where is the Iranian nuclear program now?”

He has a point. The original rationale for NATO’s anti-missile system was defense against long-range, nuclear-armed missiles Iran might develop. As President Obama said in 2009, “If the threat from Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile program is eliminated, the driving force for missile defense in Europe will be eliminated.” And indeed, thanks to the 2015 nuclear accord, Iran is currently unable to produce material for a nuclear bomb. Meanwhile, previous missile threat estimates have also been proven wrong: Iran’s missiles remain limited to medium-range, and there is no indication of its intention to extend their reach.

However, like Wile E. Coyote running past the end of the cliff into thin air, NATO’s missile defense project keeps going even as its grounds disappear: in May, construction of a new missile defense site began in Poland, with the purpose of extending the capacity against the nonexistent threat of intermediate-range missiles.

Although Iran could break out from the nuclear deal, it would take at least two years for it to produce one nuclear warhead, and even longer to develop long-range missiles. This would leave ample time for NATO to respond later, as the current phase in Poland is scheduled to take only two years.

NATO officials now justify the project in terms of the generic threat of missile proliferation, referring to 30 countries possessing or seeking missiles that could carry WMD. They fail to mention that the only country with intermediate-range missiles capable of reaching Europe is Israel. In short, there is no security rationale behind NATO’s current missile defense policy.

Most Europeans do not care, because it has always been the Russian bear rather than the Iran scare that drives their anti-missile enthusiasm. Countries like Poland want to host missile defense components because a U.S. military presence eases their anxieties about Russia. Unfortunately, missile defenses provide a false sense of security, as they invite more tensions with Russia – which recently placed Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad to target the Polish site.

Europeans also tend to dismiss Russian concerns. Americans, who placed Soviet missile defenses on their Cold War nuclear target lists, should know better. However, particularly after the George W. Bush administration withdrew the U.S. from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002, the White House has downplayed this problem, viewing missile defenses as inherently benign.

Trump has a unique opportunity to start correcting past mistakes by halting the construction of the unnecessary Polish missile interceptor site. Showing long-overdue restraint on this key strategic issue would improve European security and save hundreds of millions of U.S. taxpayer dollars, both of which might appeal to a president-elect who believes U.S. allies are freeloaders. And there are less costly ways to reassure the Poles, such as stationing U.S. troops in Poland as a tripwire.

This could also pave the way for dramatic nuclear reductions. As Steven Pifer from the Brookings Institution recently noted, “A future U.S. administration interested in a treaty providing for further cuts in strategic nuclear forces may find that it can go no further if it is not prepared to negotiate a treaty on missile defense.” Trump might want to check in with Henry Kissinger on the interrelationship between strategic arms limitation and the ABM Treaty in the 1970s.

There are too many unknowns to predict what Trump will do in office. However, if the president-elect is serious about changing U.S. relations with Russia – and if he comes to understand the value of the Iran nuclear accord – he might be able to conclude a deal that eluded Obama and improve NATO security.