<<As part of the Feasts project, and the “Make an Everyday Meal Utopian” strand of it, we’ve asked people with a wide variety of expertise to contribute some pieces which might be of interest to anyone setting out to add a salting of utopia to their daily bread. The pieces won’t be anything as standard or straightforward as a set of recipes to be followed mechanically; but rather, a series of fresh ingredients to be stirred into the mix, as anyone wishes, and if they see fit.>>

Banquets and funerals were the only means to express public criticism of the Orleanist regime after 1834-5 when all politicial associations and even the word ‘republic’were banned. Reform bills to extend the suffrage below a 200 franc a year tax payment or exclude holders of public office from the Chamber of Deputies (40% held public office) or alter constituency boundaries to enfranchise more northern urban citizens, were a regular feature of the 1840s. The Chamber rejected all, with substantial minorities, with equal regularity.

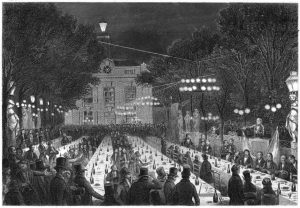

Reformers tried banquets and petitions. The cost of a banquet was usually four francs, which bought an apology for food (no details on what was consumed, no-one seems to have illustrated a single feast), wine for toasts, followed by reform speeches. The price (and perhaps limited alcohol) confined them to prosperous non-riotous citizens. In 1840 a petition and banquets to enfranchise all National Guardsmen, was dismissed by the Chamber. In Britain Chartists were demanding franchise reform, with no greater success. In May 1847 a banquet and petition campaign was announced for the parliamentary recession after a bill to enfranchise 100 franc tax payers was rejected. The campaign began and ended in Paris, spear-headed by the republican publisher Pagnerre and the 1846 Seine electoral committee. Some of the more moderate leftwing deputies, including Thiers, Dufaure and Rémusat, refused to join, considering an appeal outside parliament illegal. Only a minority of the deputies who had voted for reform took part. The reformers took counsel from Cobden, then on a visit to Paris, on the organisation of his successful extra-parliamentary endeavours in Britain. At first the banquets were organised and dominated by the dynastic left anxious for modest suffrage reforms which might give them a better chance of ousting Guizot. Initially Odilon Barrot was the most sought-after, speaking at eight banquets. The first, at Château-Rouge in Paris on July 9 1847 was a sell-out, with over 1,200 subscribers. Invited speakers expressed generalized support for moderate reform and criticised corrupt practice; it was hard to go further since reformers could not agree on who should be enfranchised. Given the contemporary serious economic depression and the support of socialists such as Louis Blanc, there were also speeches in favour of social reform.

Only a limited number of departments had the will, means or personnel to run their own banquets. Those towns with an opposition newspaper or deputy imitated Paris. The Seine committee provided lists of speakers. Banquets were presided over by local notables, the opposition deputy was always a central figure. The mayor, as in Saint-Quentin, might take the chair; the president of the Chamber of Commerce, as in Saintes and Saint-Jean-d’Angély, might make one of the speeches. Members of local departmental councils were prominent; it should be recalled that 16 departmental councils had voted for electoral reform in their annual meeting that year. All sixteen, including Aisne, Côte-d’Or, Moselle, Nord, l’Oise, Haut-Rhin, Saône-et-Loire, Seine and Vosges subsequently held banquets.

A toast to the `king of the French people’ was taken before the speeches. Some banquets were moderate, some almost exclusively republican, although the most left-wing elements around Ledru-Rollin, editor of Le Réforme, initially refused to cooperate with monarchist organisers. By the beginning of November twenty-two banquets had been held. A banquet planned for Lille on 7 November attracted over 700 subscribers. Ledru-Rollin was persuaded to speak, to the chagrin of Barrot and others who deplored his emphasis on workers’ rights and social reform. Angered at his presence, the moderates withdrew. Ledru-Rollin was warmly applauded when he spoke of the need for democratic republican and social reform: `I say that those who pay the taxes of blood and sweat and silver have the right to participate in the government which disposes of all these riches. He ended with a toast to `the improvement in the condition of the working class’. The involvement of Ledru-Rollin signified an escalation of the campaign. Toasts to the `right to work’ were made in Valence and Castries.

Victor Considérant, socialist editor of Démocratie Pacifiqueand member of the departmental general council of the Seine, assured those who attended the banquet in Montargis on 22 November that social reform was urgent to avoid serious conflict. None of the various bourgeois factions had close relations with artisan groups. The parameters of political reform were just as fudged and ambiguous. Ledru-Rollin made no secret of his championship of universal male suffrage, nor of his affinity with republicanism. Would the former necessarily involve the overthrow of Louis-Philippe and the creation of a republic? Radicals of a jacobin-bent had no doubt of this, but others were far from convinced, especially as such a strategy was unlikely to be achieved by reform, discussion and peaceful means. Thus radicals were not only few in number, with almost no appeal outside Paris and the larger towns, they were often far more at war with each other than with the Orleanist regime.

After the Lille banquet, Ledru-Rollin and his associates, competed with the original monarchist moderates for control of a reform movement which thus became very divided and with no clear message. On November 21st Ledru-Rollin took part in a second radical banquet, this time in Dijon, a city known for its leftwing preferences; the republican Mauguin and the republican socialist Etienne Cabet had both served as deputies for Dijon during the July Monarchy. As many as 1,300 radicals attended and listened to speeches by Arago, Louis Blanc, Ledru-Rollin and others. Universal suffrage, the sovereignty of the people and the Convention were all toasted in terms which disturbed more moderate reformers. On the 26th it was the turn of Lyon and a banquet with a more moderate tone and an even larger attendance, 1,600. On 19 December at Chalons-sur-Saône Ledru-Rollin offered an indisputably republican mouthful of a toast `To the unity of the French Revolution, to the indivisibility of the Constituent Assembly, the Legislative Assembly and the Convention’. The pace of the campaign quickened as it grew near to the end of December when parliament would re-assemble; fourteen moderate banquets were well-attended in different areas, despite the colder weather. The Rouen banquet held on Christmas Day urged campaign unity. Duvergier de Hauranne, a moderate reformer, stressed the need for reform to purify the electoral system so that national, rather than individual and local interests predominated.

The banquet campaign did not seem to alarm the government even though some 70 banquets were held between July 1847 and February 1848 in which 100 members of the Chamber of Deputies and more than 22,000 subscribers participated. They were geographically concentrated in twenty-eight traditionally radical departments in the Nord, the Paris, Saône and Rhône regions. Some banquet organizers encountered obstruction, but not prohibition, despite the pronounced popular unrest of these months provoked by the economic crisis. Journalists were prosecuted for their radical reports of banquets, officials were castigated for their participation.

Assuming that perhaps four times as many people heard the speeches as subscribed to the banquet, the campaign, while the largest of its kind in the years of the constitutional monarchy, did not force Guizot’s hand. The government seemed to assume that the king’s popularity would preserve him and them, an assumption which was echoed in the speech from the throne on the opening of parliament on 28th December when Louis-Philippe criticized the `hostile and blind passions’ that were stimulating unrest. The deputies who supported the banquet campaign defended the legality of their actions in the debate on his speech, although the Peers seemed more interested in reform than the lower house. An often-quoted (especially by its author) speech of 27 January was exceptional. Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-59), a liberal theorist, already well-known for his study of America and his criticism of the Orleanist regime declared `the wind of revolution is in the air’. The government had completely failed to take any account of the serious social problems and there was an atmosphere of moral decay in public life itself. The spirit of the government, he proclaimed, `is dragging us to the abyss’. His colleagues dismissed his warnings, observing that Tocqueville was always a prophet of doom.

It was not until February 7th that the Chamber of Deputies returned to its debate on the speech from the throne. The government was now sufficiently worried by the banquets to consider a total ban. The large attendance at banquets was, suggested Barrot, a fair indication of the strength of public feeling; the refusal of the government to pay attention left it prey to more violent means. Ledru-Rollin quoted the Declaration of the Rights of 1793, which defended the right of assembly, in his view, a natural right of man. However a conservative amendment to the speech from the throne demanding a debate on the whole issue of parliamentary reform and that the government introduce a `wise and moderate’ bill of its own was rejected by 222 votes to 189. In mid-February the traditional address to the speech from the throne was supported by 241 to 3.

Outside parliament the subject was not dead. On February 9 Ledru-Rollin threatened to revive the idea of a strike of tax-payers which had been mooted shortly before the 1830 Revolution. A number of banquets were held during the weeks when the speech from the throne was under review, including a revolutionary communist one in Limoges. It reflected the idiosyncratic ideas of the organizer, the utopian Théodore Bac. A predominantly republican banquet planned for the Latin Quarter of Paris in mid-January was postponed on the orders of the police to February 22nd. The banquet was planned by the officers of the 12th legion of the National Guard, one of the most radical, being in part recruited in the workers’ district of Saint-Marcel. To make the occasion more acceptable to the authorities the price of a ticket was raised from 3 francs to 6, attendance was restricted to qualified voters and the locale was shifted, the Saint-Marcel area being considered too volatile. Ledru-Rollin was scheduled to be one of the chief speakers, but withdrew when eighty other deputies declared that they would not attend if he did. Finally the organisers were ordered to cancel the banquet whenLa Réformeannounced that the banquet would be preceded by a march of the unemployed. On February 21st the Chamber of Deputies was forced to return to the subject by pressure from the reform group within its doors. Barrot urged a full debate, but the Minister of the Interior, Duchâtel, continued to muzzle any discussion, arguing that the ban on the Paris banquet had to be maintained because of the threat of the accompanying mass demonstration.

Other factors ensured that the cancelled banquet was now bound to be used as a vehicle for advertising broader, and in some ways more pressing, problems. The social impact of the prolonged economic crisis contributed far more to de-stabilising Louis-Philippe’s France than the banquet campaign. A second republic would never have emerged from a cancelled banquet, had it not been for the severe economic depression of these years. Before the February Revolution, 1848 a republic was not on the immediate agenda of even republicans. Uncompromising republicans were a tiny fringe, some middle class lawyers and journalists, some modest businessmen and some artisans. The Second Republic was the product of economic crisis and Orleanist panic, an abdication rather than a seizure of power; a scenario very reminiscent of 1830. However, it should be noted that, although the banquet campaign alone would never have led to a republic, it was frequently the leaders of the campaign in Paris and especially in the provinces, who took control once Louis-Philippe had been replaced by a democratic republic.

Pamela Pilbeam is Professor Emeritus in French History at Royal Holloway, and a sessional lecturer at Birkbeck. She is the historical consultant and main presenter of The Legend of Madame Tussaud, an Arte docu-drama seen on BBC Four, 23 February 2017. Her recent books include Madame Tussaud and the History of Waxworks (2003), Saint-Simonians in Nineteenth-Century France (2014) and The 1830 Revolution in France (2014).