BY BONNIE LATIMER

One of the funniest texts of the mid-eighteenth century is Jane Collier’s acerbic An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting (1753). Collier sardonically imagines that most people’s true goal in life is ‘to plague all their acquaintance’.

She helpfully lays down rules for doing so, encompassing masterpieces of passive aggression—for example, she advises deliberately ruining days out through strategic fakery of headaches or the ‘unaccountable disorders’ of women. With typical eighteenth-century black humour, she suggests spoiling one’s children so that they will grow to be a torment to themselves and everyone else, and praises those so pettily vindictive that they will ‘hang themselves to spite their neighbours’.

Collier is not only mocking the sort of social martyrs one may still encounter today, but satirising a characteristically early modern genre: the conduct book. Neglected today, conduct literature of all stripes was written and read appreciatively in the eighteenth century. To understand a little more about this type of writing and its complexities, it is worth looking at the man who printed Jane Collier’s essay: Samuel Richardson.

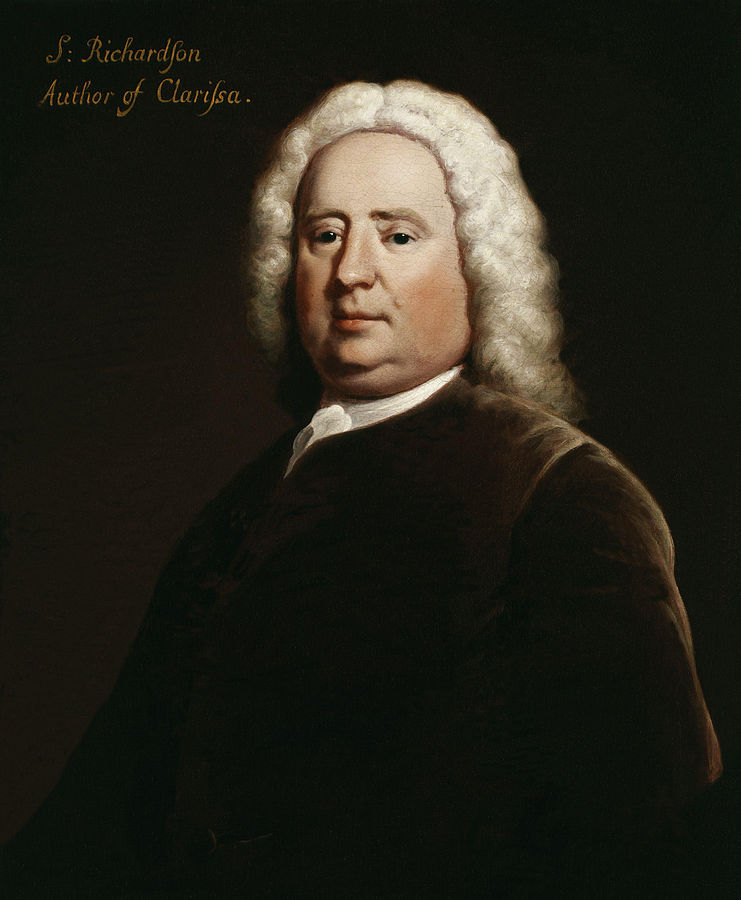

Samuel Richardson (1689-1761) is popularly known as the author of Pamela (1740), Clarissa (1747-8), and Sir Charles Grandison (1753-4. He is a key precursor to Frances Burney, Jane Austen, and George Eliot. An aspect of his career which also interests scholars, however, is his work as a printer.

Richardson was a businessman who understood the book trade; he actually regarded his novel-writing as a ‘leisure’ activity. He was well-positioned to know what sold, and it was from this perspective that he produced his earliest writings, which are all forms of conduct literature.

A key text is The Apprentice’s Vade Mecum (1733). This was originally written with his own nephew, Thomas Verren Richardson, in mind. Tom Richardson, a teenaged lad, was set to join his uncle’s business as an apprentice; beforehand, the elder Richardson wrote Tom a guide to getting on as an apprentice, a curiously liminal position halfway between household member and employee.

Apprentices did not get paid wages; they worked for board and lodging, living in the master’s household, and were taught the rudiments of their trade. As one might imagine, the idea of a teen moving away from parental supervision sparked anxieties: the ‘retainer’ which all apprentices signed anxiously cautions them not to keep bad company, or to waste time in taverns and theatres.

Richardson’s letter to Tom encourages him to avoid the snares of older boys and city diversions, and to aim to become ‘a good printer, and a good man’; Richardson promises that one day, Tom may inherit his uncle’s thriving business.

The letter is poignant because in fact, Tom Richardson died only a few months after taking up his apprenticeship, and never outlived his adolescence. That private letter, however, provided Richardson with a template for creating The Apprentice’s Vade Mecum, a more general guide to any boys learning a trade in eighteenth-century London.

Apprentice-guides were popular: such colourfully named texts as Caleb Trenchfield’s A Cap of Gray Hairs for a Green Head (1688) typified the genre. Trenchfield saw apprentices as ‘low’, and as needing to practice constant obedience to their masters. Richardson’s approach is different. Suitably, his tone is avuncular, addressing the apprentice directly as ‘you’, and urging hard work and fair play on the grounds that one day, every apprentice will be a master himself, and will wish his own ‘Juniors’ to look up to him.

It’s significant that Richardson’s text originated with a letter. In fact, letters were often used to convey not just personal information, but advice and even public commentary. Any archive of eighteenth-century ephemera reveals many published ‘Letters to a Friend in the Country, on the Subject of’ some now-forgotten political dispute.

This speaks to a much wider interest in the ‘familiar’ letter as a means of self-expression. With the development of a reliable post office and sharply increasing literacy, more people than ever before were communicating by letter. But not all of them were confident at doing so—and that’s where guides like Richardson’s other major conduct text, the Familiar Letters (1741), come in.

The Familiar Letters is a letter-manual, offering model letters for adaptation in real-life situations, from a tenant who needs more time to pay his rent, to a maidservant being courted by a young man. Richardson’s text had much in common with the period’s many other letter-manuals—but he’s differentiated by his idea that writing good letters could make one a better person.

His manual has a ‘choose your own adventure’ quality, often elaborating scenarios such as a young lady being pressurised into marriage; here, sets of letters between her and her father show what she could write if she gave in, or if she remained stubborn. Ultimately, almost all the letters have a sound moral at bottom. Richardson believed that they offered not only epistolary guides, but ‘forms and rules to think and act by’.

All of this risks sounding awfully prescriptive, but it needn’t be read like that. The devil is in the detail—or rather, in the metaphors. Many conduct texts of the period proposed to ‘impress’ or ‘imprint’ lessons onto the mind of the reader, who would then be impelled to follow them. One might think that a printer like Richardson would warm to such rhetoric. But he doesn’t: instead, his most characteristic image for learning morality is the ‘chalked-out path’, a road or way marked out by another.

Of course, though, as any avid hiker will know, following a path involves making one’s own interpretive choices, deviating from and regaining the way, and ‘striking out thro’ overgrown underwood’, as Richardson put it in Clarissa. I see his didactic writing as animated by a tension between laying down moral rules and respecting the free will of his readers. It’s that tension which makes his didactic writing as dynamic and absorbing—if not quite as amusing—as that of Collier.

About the author:

Dr Bonnie Latimer is Lecturer in English at Plymouth University. She is the author of Making Gender, Culture, and the Self in the Fiction of Samuel Richardson (2012).