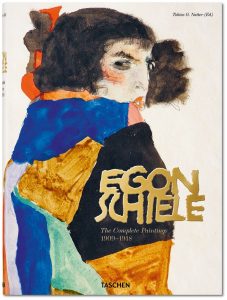

Gemma Blackshaw, Professor of Art History at Plymouth University, is an internationally acknowledged expert on the Austrian artist Egon Schiele (1890–1918). Her work on the sexual provocateur who shocked Viennese audiences with his explicit images of the naked and contorted body has been described in The Burlington Magazine as ‘densely documented, rigorously argued and delightfully astute’. Her latest research on the aftermath of Schiele’s imprisonment in Neulengbach in 1912 for the display of obscene drawings was commissioned by TASCHEN for its expansive XXL-format book, published in three languages in the summer of 2017, which surveys the complete catalogue of Schiele’s paintings from his most innovative and prolific decade between 1909 and 1918. The Catalogue Raisonné, which includes over 200 paintings and 150 drawings and watercolours, many of them newly photographed, is the first to appear since Jane Kallir’s Egon Schiele: The Complete Works of 1990, and it addresses both the significant scholarly activity on the artist in the past 30 years and the subject of provenance, acknowledged as one of the most vital areas of new research on Viennese Modernism. Exceptional reproductions of Schiele’s work are combined with images from private archives, a complete list of exhibitions of Schiele’s painting, a complete bibliography, and essays by world-leading researchers on modern Viennese art including art historians, curators and collectors. In his introduction to the book, the editor Tobias Natter, former curator of the Austrian Belvedere Gallery and director of the Leopold Museum in Vienna, draws attention to the revisionist approach which characterises Professor Blackshaw’s work and which impelled her new reading of Schiele’s most ‘private’ paintings and drawings as oriented towards the decidedly masculine public for modern art in early twentieth-century Vienna: ‘While most scholars in the past have assumed that Schiele withdrew into the private sphere after the Neulengbach affair, our author shows how he strove to transform his incarceration and exclusion from society into its opposite.’ Working across the history and the gendered historicisation of modern Viennese art, Professor Blackshaw’s essay is the latest of a series of publications which address the patriarchal structures of the market for modern art in ‘Vienna 1900’, and of modernism itself.