James Sweeting, Associate Lecturer Game Arts and Design and PhD Student with Transtechnology Research, writes:

The relationship between videogames and music is one that has developed significantly over the few decades that the videogames medium has been around for. During the early stages of the existence of videogames, music did not extend much beyond simple electronic sounds. Over the next couple of decades this expanded in complexity, but still depended on utilising carefully programmed electronic sounds to create intricate melodies that made use of the technical limitations. Despite these limitations, the composers managed to create memorable music that provided a constant background auditory experience that supported the visuals that were displayed and interacted with. It might sound hyperbolic, but for those playing these videogames, the music for these videogames became the soundtrack to their generation.

My research focuses on the connection between videogames and nostalgia, and whilst I have tended to concentrate on the visual and gameplay elements that demonstrate these phenomena, music – whilst not ignored completely – is to a certain extent underexplored more broadly.

I recently came about addressing this aspect due to a personal interest in a musical genre from Japan that has recently gained niche popularity in the West. This genre is known as City Pop and was prominent in Japan from the late 70s to the late 80s and became synonymous with the country’s Economic Bubble. I wanted to explore it further, as, despite the genre predating myself and existing in another country and culture, there was something about it that felt both familiar and somehow nostalgic; and I was not alone with others sharing this same sentiment. YouTube user Van Paugam in a description for a video compilation of City Pop music they uploaded to the site wrote about this about the genre:

‘Memories flood your mind when you first hear it. Are they your memories? Who’s memories are they? Why does it feel like you’ve heard these songs before?’

The emergence of City Pop in the West has been the result of its music being discovered on YouTube, with Mariya Takeuchi’s Plastic Love finding its way into the suggestions of many users on the video sharing site. It now has over 20 million views and has exposed many people to a genre of music they were previously unaware of.

I hypothesise that a possible reason for my perceived familiarity with the genre could be to do with my interaction with Japanese videogames and to a lesser extent Japanese cinema and anime. But it’s the music from the former that has also experienced a resurgence, one that has a nostalgic tendency that is easier to identify.

For videogame website Kotaku, Luke Winkie writes about how the Nintendo 64 (which was released in 1996) has gone on to see people use music, sound effects, and footage from videogames available on that system and remix it into a hazy Dreamwave-esque (Dreamwave can also bring up nostalgic connotations) audio-visual experience. This is also in line with observations made by Jonathan Rozenkrantz for the open access journal Alphaville titled “Analogue Video in the Age of Retrospectacle: Aesthetics, Technology, Subculture”. The main goal of his piece was to highlight how the artefacts of analogue video from the 1990s have been used by creators in the 21st century in creating work that evokes nostalgia for that media.

Analogue video is an interesting media to explore, as storing audio-visual on magnetic tape, despite in consumer technology having now vanished (it was discontinued in the West a decade ago) is only around four decades old. Therefore, the technology has not been around all that long and has already seen three types of digital optical disc-based storage succeed it; as a result, there are those whose nostalgia for the medium has been generated because of the sense of loss for it. This is also supported with the shift away from CRT (cathode ray tube) televisions to LCD/LED/Plasma flat panel televisions and the digital inputs associated with them.

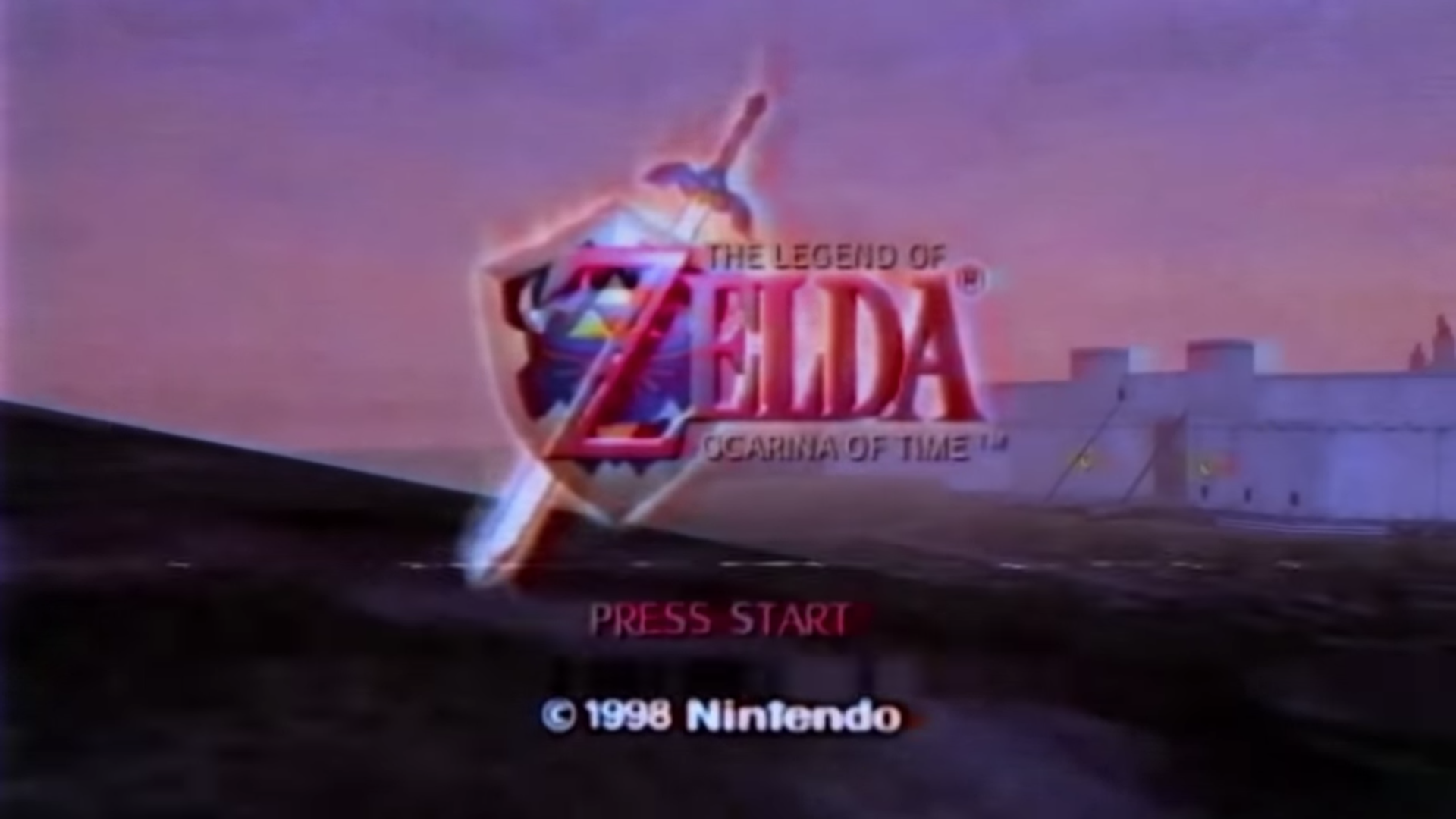

This combination has contributed to the desire among some to try and reclaim the lost aesthetic of the 1990s regarding the videogames that were available at the time. Whilst videogames such as The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) have been re-released in the years since and can be played on other Nintendo systems (and even remade to support stereoscopic 3D), it is difficult to recapture that same experience today.

Like the examples that Rozenkrantz identifies in which the signs of tape deterioration are preserved and transferred to digital code to enable the nostalgic signs to be remediated and re-appropriated, the same can be seen in the YouTube remixes of music from Ocarina of Time and the presentation of the video that accompanies the music.

There is a caveat though that I need to address. Nostalgia of media might be impacted by the time the referent was created – in this instance the mid to late 1990s – but on an individual level, it will be when that referent was engaged with. In my case, whilst I do have what can be considered nostalgic leanings towards Ocarina of Time, this is not for the late 1990s, instead it is for the early 2000s when I played the rereleased version on the Nintendo GameCube.

I am not alone in this, as there will be many others who have played Ocarina of Time in the years since its initial release and will subsequently have some affinity for the game and its aesthetic elements. The extent to which someone who did not grow up in the 1990s enjoying the remix video might not be as considerable as someone who did, but that does not mean that an attraction to related content created with nostalgic tendencies in mind does not have appeal. This line of thinking could also explain the appeal of City Pop and its importance now, despite its heyday occurring more than three decades ago. Its influence lives on across Japanese media, which in turn has contributed to global culture in its own small way.

Then again, one could state that consideration of whether something is good is a determining factor, but what disregards this is that interest in these videogames and music is predicated on the fact that they are not new, even if they are new to some people engaging with this media. The age and the aesthetic style these media pieces are depicting are not a product of this decade and even though there are imitations or works that take their inspiration from them, it is the aspect of being from another time, be one that is lost and rediscovered – or discovered for the first time that distinguishes them.

(Image credit: Marble Pawns. (2017). Zeldawave. Retrieved November 28, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bHUvykXL8Og)