By Jody Patterson

In the aftermath of unleashing a new arsenal of atomic weaponry on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 American artists struggled with the question of how to respond to the unprecedented atrocities of nuclear warfare. What could they say in the wake of the carnage wrought by the militarization of science for such inhumane purposes?

As the world struggled to grasp the bomb’s scientific, political, military, and moral implications, one of the major dilemmas for artists was how to represent the unrepresentable.

Ralston Crawford (1906-1978) was among those artists seeking to engage the new realities of the postwar world. During WWII, Crawford served as Chief of the Visual Presentation Unit of the Weather Division in the Air Force. His mandate was to develop a visual language of easily recognizable symbols to indicate rain, snow, clouds, and other meteorological conditions so that military personnel would have iconographic representations of the weather.

After his decommissioning from the military in 1945, Crawford became aware of the nuclear testing scheduled to take place in the summer of 1946 at Bikini Atoll, a remote locale in the Marshall Islands captured from Japan in 1944 during the US campaign in the South Pacific. He successfully lobbied the Art Director at Fortune magazine to send him to Bikini as an artist-witness at Operation Crossroads, the name given to the tests at Bikini.

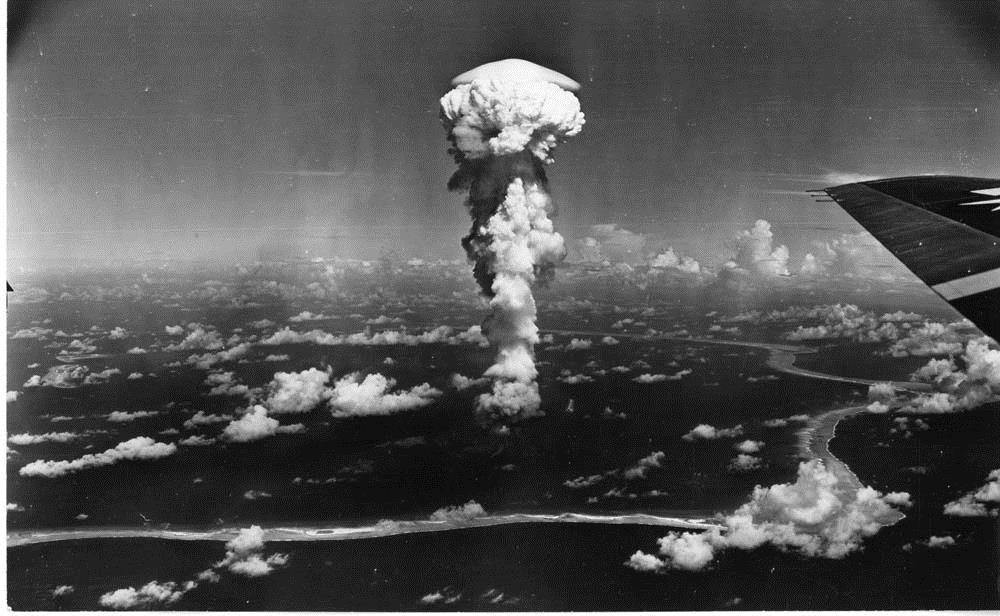

Test Able, Operation Crossroads, Bikini Atoll, 1 July 1946

Operation Crossroads consisted of two detonations: Test Able was detonated in the air on July 1; three weeks later Test Baker was detonated underwater. Taking place in the murky twilight of the Cold War, the tests occurred in a highly charged political context as ties with the Soviet Union deteriorated and the UN debated how to establish control over the use of atomic energy.

In contrast to the wartime stealth demanded by the atomic detonations in 1945, the Bikini tests were the first to be publicly announced beforehand and observed by an invited audience, including a large press corps and artists such as Crawford stationed 18 miles from the perimeter of the target fleet. The detonations were conveyed to the world via radio broadcasts, newsreel images, and the circulation of thousands of photographs in the popular press. Crawford’s response to Operation Crossroads appeared in the December 1946 issue of Fortune.

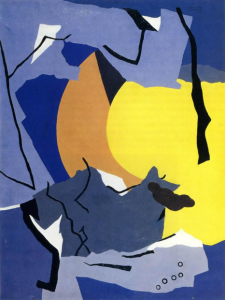

Just as Crawford’s weather maps for the Air Force demanded the translation of unpredictable and ever-changing forces into a planar lexicon of graphic symbols, his work for Fortune entailed developing a visual language that captured the magnitude of the atomic blasts and their lethal aftereffects. Many of these, such as the deadly beta and gamma rays released into the atmosphere by the detonations, were invisible. As is evident in Test Able, Crawford exploded space, fused figure and ground, fragmented form, and scattered brightly coloured shards across the picture plane.

Ralston Crawford, Test Able (1946)

Ralston Crawford, Test Able (1946)

Although Test Able initially appears entirely abstract, his modernist rationalism and contrived manipulation of form and color remain sufficiently tethered to visual reality to identify an aerial view of the detonation, including the salmon-hued cloud of the explosion, the yellow haze of radioactive particles, the contrasting blues of sky and lagoon, and the grey of torn navy vessels recognized by their port holes.

Crawford’s paintings were greeted with a mix of incredulity, misunderstanding, and ridicule. However, extant treatments continue to view them in isolation from the interpretive context of the Fortune article such that much of their meaning and particularity is lost.

Firstly, Crawford insisted that the paintings were published alongside documentary photographs and explanatory texts, thereby rendering a literal picturing of the blasts redundant. As he asserted, it would be “pointless to paint the bombing realistically” since “photographs do a much better job reproducing it physically than a painting ever can.”

Secondly, he was interested in a “broad democratic method of distribution” for art, making dissemination in a magazine more effective in reaching an audience than the easel painting. Finally, it was never Crawford’s intention to directly transcribe the detonations in the South Pacific.

Echoing the sentiments of political writer Dwight MacDonald, Crawford agreed that naturalism was “no longer adequate, either esthetically or morally, to cope with modern horrors.” Crawford maintained “the millions of words and miles of photographs emanating from Bikini generally imparted no more than the most superficial and external record of this profound and terrifying experiment.”

In response to efforts of government officials to “humanize” and “normalize” the bomb by claiming that it was “simply the latest step in man’s long struggle to control the forces of nature,” and in an attempt to counteract the complacency resulting from the numbing effects of media saturation, Crawford was also keen for his Fortune commission to serve a purpose, to be useful in the same way as his weather maps were able to translate invisible forces into effective graphic symbols.

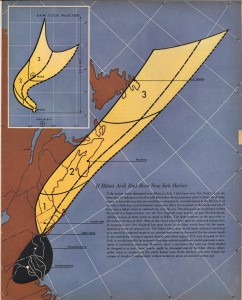

‘If Bikini Atoll Had Been New York Harbor,’ Fortune, December 1946

He insisted on designing a map that pictured the extent of radiation poisoning and fall-out that would accompany bombs such as those detonated at Bikini if dropped over a densely populated region on the eastern seaboard. Taking up Macdonald’s point in an editorial for Time magazine titled “Descent Into Barbarism,” the “real horror of the Bomb is not its blast but its radioactivity.” Crawford was thus seeking to make the imperceptible visible to American audiences.

For Crawford, art could not, and should not, passively re-present the new realities of the nuclear era. Rather, painting could be used to formulate an analogue of contemporary experience through the rational and considered use of form, colour, and composition, and thereby serve as a medium of communication that was both visual and ideological.

Crawford met the bomb’s capacity for destruction and chaos with the artist’s capacity for creation and order. Logic and reason were what was needed as history stared into a moral and technological abyss.

About the Author:

Dr Jody Patterson is Associate Professor (Senior Lecturer) in Art History at Plymouth University. Her research interests include visual arts and cultural politics in the United States; international mural painting and public art; New Deal Art Programmes; and state art and culture during the 1930s.