The following was written by Gemma Blackshaw, Professor of Art History, for the major exhibition Chantal Joffe: Personal Feeling is the Main Thing at The Lowry, Salford (19 May – 2 September 2018), which displayed new and recent paintings by Joffe alongside paintings by Paula Modersohn-Becker.

Sunday 11 March

I woke for the first time this morning at a little after three. My daughter, who has started to sleep alone, had called out for me, and then for water. I held the cup in one hand, the back of her head in the other, leaning over her kneeling body, murmuring something. She drank deeply and then fell forwards on to the pillow, eyes closed. As she turned on to her side and felt my hand on her cheek, her ear, her hair, she said what she has said on every waking since leaving my bed six months ago: ‘Mummy, you stay there.’

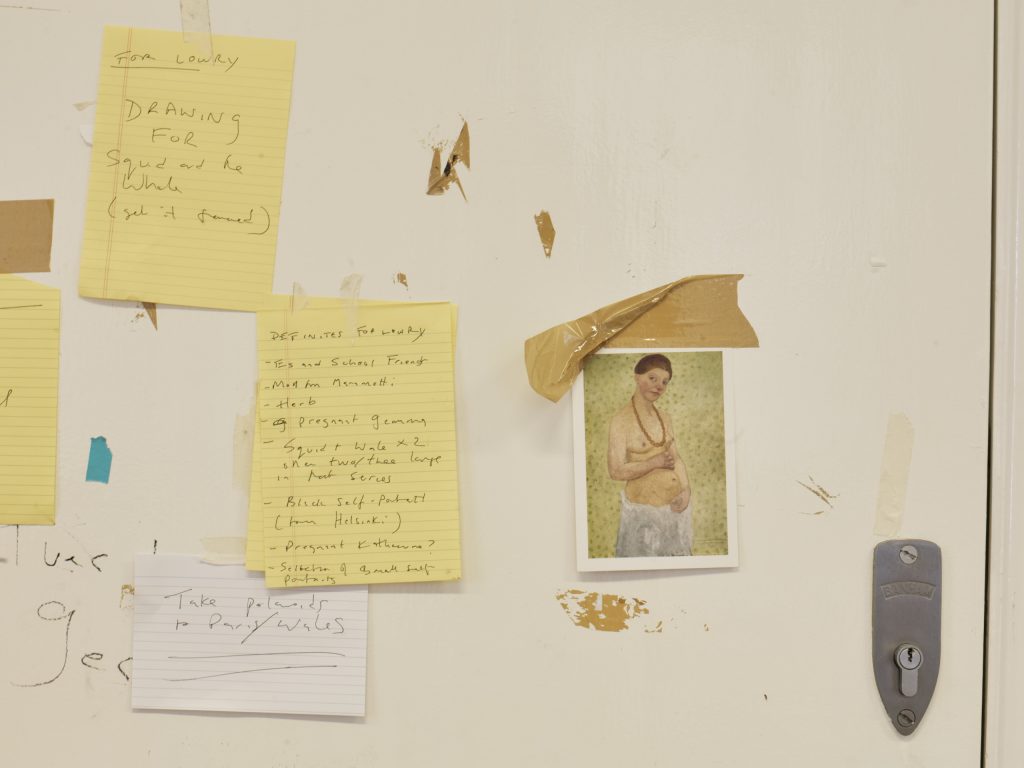

I met the figurative painter Chantal Joffe in the midst of the assisted fertility cycles which would lead to my daughter, who is two years old, and my son, who will be born seven weeks from now. The tensions between the desire for a child and its fulfilment, between dependence and independence, between staying there and going away, lie at the heart of our conversations about painting, reading and writing. Our collaboration on a series of images produced during the sixth, seventh and eighth months of my second pregnancy, at forty-one years of age, arose as much from these exchanges as from our interests, in our respective domains, in the problematics of the nude in modern European art, and in those artists who embraced them as the subject of their work. Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876 – 1907), the German modernist who devoted herself to paintings of women and children, is one of Joffe’s most significant influences. Working in the first decade of the twentieth century, within a society which distinguished male creativity from female fecundity, Modersohn-Becker struggled to conceive of her body as being that of both artist and mother.

Her celebrated image of her half-naked self with a rounded belly she encircles with both hands has been interpreted as profoundly ambivalent, the product of a ‘rupture between the role of the artist and the role of the mother’, which was as cultural as it was personal.[1] ‘Paula’, as Joffe calls her, did not have the time to reconcile the two, dying of a pulmonary embolism when her physician deemed her fit to stand, eighteen days after giving birth to her first child, Mathilde.

Would it have been just a matter of time? I like to think so, however contrary that might be to the efforts we know early twentieth-century female artists expended on establishing geographical, if not emotional distances between themselves, their children and step-children in order to pursue their practice, Paula and her close friend, the sculptor Clara Westhoff (1878 – 1954) included. This is why I sit for Joffe, whose paintings of herself, her mother and sisters, daughter, nieces and female friends seem to me to both register and resist the separation of ‘life and work’, realising the creative potential in being ‘divided’.

Monday 12 March

I woke for the first time this morning at half-past four. ‘Mummy, you stay there.’ On the third waking, at half-past six, I changed my daughter’s nappy and carried her, bare-legged, into my bed. We lay on our sides on the same pillow, facing each other. She fell asleep again, her arms flung about my neck, my son’s heels drumming against her shins.

My body is not my own. My experience in pregnancy of the loss of self, however illusory that sense of selfhood may be, has made it easier to undress and sit for Joffe, to submit to the objectification that is intensified in the life-study experience, no matter the gender or sexual orientation of the artist, or how participatory the process, and to look at the images that ensue. Joffe sometimes works from photographs, which enable her to capture the energy and dynamism of subjects who won’t stay still for long: of girls in a playground, laughing, mid-lollipop; of toddlers pitching out of sofas and paddling pools; and of her daughter, standing, it seems, for no longer than it takes for the finger to activate the camera before running, ever-busy, from the room. Her practice as a figurative painter is in many ways generated by the taking, giving and sharing of such images, a folding of life into work that draws deeply upon family and female friendship, shared emotion and experience. She painted from the first photograph I took of my daughter, wrapped in the white cellular blanket I’d bought the night before my induction of labour; for the representation of my newly pregnant body, however, she chose to work from life.

I arrive at the studio at 10 and drink a mug of tea by the sofa or chair she has set up within an arc of electric heaters which continually blow fuses and trip circuit breakers. We talk about our daughters, their fathers, the cold, and as we’re talking I take off my coat and shoes and dress and bra, and ask about the tights – on or off? We think on their formal qualities; we decide on, then maybe off. The position I sit in is the one that’s most comfortable. There is no ‘pose’, no sense of display. Joffe might suggest a twist to emphasise the curve of my belly, a lift of an arm to create some negative space, but nothing more. She sits on an oil-encrusted office chair with wheels, a little higher than me, at a distance of three or so metres. When she rolls across the floor on it, looking at me from a new vantage point, she scolds herself for not doing so earlier: why should I move, when she could move? Her attentiveness is absolute.

She begins by working on paper, drawing my outline with thin sticks of charcoal on a pad propped up on her knees. The sheet is never big enough: its top and bottom edges cut across my head, my neck, my knees, my ankles, and this is characteristic of Joffe’s practice, evoking the family photographs which so inspire her with their awkward, accidental crops and distortions. The first drawings are almost always discarded, ripped from the pad and placed face-down on the floor, often with nothing more than three lines upon them. They become more detailed as the sitting develops, and as we stop talking. When she focuses on my hair, my fingernails, the pattern of my lace tights, I know that she is entering what she has described as an altered state of being, when her eyes and hands and materials seem to work together of their own accord, bypassing the mind’s anxieties about performance that are heightened by the presence of the subject.

She could go on and on in this state but her mobile buzzes: a text from a sister; a photo from a friend who has just given birth. She sees the time: Esme needs to be met from school; when is my train; who is staying with my daughter? We eat egg mayonnaise sandwiches whilst standing up, appraise the sizes of the canvases and boards she has prepared, think about what’s feasible in the remaining two, three hours.

Tuesday 13 March

Four o clock. Five o clock. ‘Mummy, you stay there.’

Joffe paints quickly on surfaces primed in lurid green, lilac, or, more recently, a deep, rose pink. Ordinarily, she’ll begin with a rough outline which is often wiped off and replaced with another; on occasions, she’ll start with an eye, a mouth or an ear, ‘wrong-footing’ herself in order to push her practice in a different direction (she adopts a similar method with her brushes: Joffe is left-handed but will use her right in pursuit of a different mark or quality of line). Her brushes are large and long-handled, upended in a variety of vessels that stand on the glass table top she mixes her oil paint upon. She holds those she is not using between the fingers of her right hand which ensures that she is balanced, and that the colours – the black, the white, the pink, the blue – are kept ‘clean’. As the painting progresses the brushes increase until there are nine, ten, eleven in one fist. The pigment is combined with cold-pressed linseed oil, poured into a plastic takeaway box; when the outline is clear and the flesh tones complete she applies a much thinner consistency of paint to the band of my maternity tights, sitting back with her head on one side to look at the rivulets that run down the surface, exposing the vivid green ground underneath. This is her only pause. The painting takes an hour, maybe two.

Thursday 15 March

Half-past seven. I wake on hearing a car in the street. My first thought, on seeing the light that steals its way around the bedroom blind, is that something is terribly wrong. I rush to my daughter’s side and lift her, warm and sleepy, from the cot. ‘Mummy’s here,’ I tell her, ‘Mummy’s here.’ Over and over again.

Joffe names her subjects: Esme; Ishbel; Bella; Moll. There are no ‘nudes’ in her work, though the naked bodies of herself, her daughter, her friends and friends’ daughters are those she continually returns to, their ageing a marker of her development as a figurative painter. I ask what she will call the images she has created of me, paintings and drawings which ultimately contest the categories and hierarchies of the history of art by dissolving the boundaries between portrait and nude, subject and object. ‘Gemma Pregnant’, she replies, ‘or Gemma Seven Months and so on.’ In her note, there is no comma to separate my name from my state of being pregnant, no punctuation to mark the experience of division which rose from my having a child. I am both myself and someone else’s mother and these identities, Joffe’s paintings propose, can be reconciled.

In her reflections on one of Paula Modersohn-Becker’s last paintings, the art historian Rosemary Betterton describes the naked, sleeping figures of mother and child, curled around each other’s forms, as a representation of ‘a subjective space in which self and other are inextricably linked’.[2] The conflict Modersohn-Becker described in her diaries and correspondence between wanting to be both herself, an artist, and a mother, is, Betterton argues, resolved in this late image, but such a process could only take place ‘in a Utopian space outside the realm of the social’: nothing in the picture identifies the woman as an individual with her own history, and this implies that there is no such resolution in the world beyond the limits of the canvas. Ultimately, Joffe’s pictures, created over one hundred years later, give me hope in this world. Painted in our patterned knickers, identified by our names, we women have our own histories, and our own means of telling them, in all their wonderful, wearying complexity.

References:

1] Rosemary Betterton, An Intimate Distance: Women Artists and the Body, London: Routledge, 2013 (first published 1996), pp. 24-25. Modersohn-Becker inscribed her self-portrait with the words ‘I painted this at the age of thirty on my sixth wedding day. P.B.’, which dates it to 25 May 1906, her fifth wedding anniversary. She gave birth to her daughter, Mathilde, on 2 November 1907. The pregnancy she represents here did not, therefore, lead to a child. Rather, the self-portrait was painted during a period in which she questioned her commitment to her marriage and her desire for a child.

[2] Betterton, An Intimate Distance, 41.

*****

Gemma Blackshaw is Professor of Art History at the University of Plymouth. In 2014, she co-curated The Nakeds at Drawing Room, London, which included work by Chantal Joffe. Blackshaw and Joffe have been in conversation ever since about the modernist tradition of painting, portraiture, and that most-contested genre of Fine Art, the nude.

*****