BY ALAN BUTLER

In retrospect, one of the more surprising things that characterised my PhD project was the need to continuously negotiate and renegotiate a variety roles, along with their associated labels. Some of these, I must admit, did not always automatically sit comfortably with me.

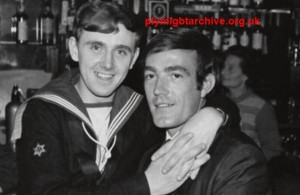

My thesis, “Performing LGBT Pride in Plymouth, 1950 to 2012,” considered how the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered communities of Plymouth performed and signified their own cultures and identities, based on the analysis of materials which were generated through archival research and through the collection of oral history interviews.

These interviews, in conjunction with previously uncovered archival memorabilia, now form a specific collection at the Plymouth and West Devon Record Office, reflecting the lives of LGB and T people in the city. The creation of the Plymouth LGBT Archive was intended to enable the heritage of these communities to be explored, via the living memory of the people who were part of it, during the 60 year period in question.

In working on this archive, and through the sharing of stories which others have shared with me, I have been challenged to represent, initially, the label of ‘gay man’ (in a far more public manner than I ever had before), ‘archivist’, ‘PhD researcher’ and, on occasion, an ‘activist for change’.

Despite my own reservations around the latter label, I acknowledge that my story has intertwined with the stories of others and that some changes have occurred during the duration of this project for the LGB and T communities of Plymouth. Consequently, I have worked with individuals who have come to take some pride in their place in Plymouth’s past and, as a result, now feel more empowered about their present and future.

For instance, the past five years have seen a re-emergence of Pride as a yearly festival in Plymouth, which I help to organize. This event provides an ongoing manifestation of individuals’ personal pride. Pride in their place in the city, and its history, as a moment of time and space is claimed for the performance of identities which can still lack visibility.

LGB and T histories tend to be performed and displayed in the moment. Traditional archival materials, such as diaries and letters, have played a lesser role in these historical narratives as individuals often sought (or had) to conceal this aspect of their identity. As a result, archiving those stories is challenging and often needs to occur through a subsequent performance in the form of an oral history interview.

The oral history archive can also be considered an intervention, providing the means to pass stories from one generation to another. LGB and T narratives tend not to be transmitted through normal intergenerational channels, as LGBT young people are seldom born to LGBT parents, so the archive provides a means of capturing these narratives from one age group and then sharing them with subsequent generations.

On 14 April 2016, I attended the Connected Communities Creating Living Knowledge event in London, which was arranged by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) to explore how best to support positive research collaborations between universities and communities.

The event included the launch of the Creating Living Knowledge Report which was derived from lessons learned from over three hundred projects from the Connected Communities Programme and sought to begin a network to lobby for sustained support for community-university partnerships in future.

In the sharing of projects, methodologies and experiences, the people in the room struggled with the labels which had defined their work and their positions within it. In working groups, many quickly felt the need to define their own roles. Some were academics, some were funders while other referred to themselves as community workers. One gentleman I noticed had the title “Community Activist” on his badge. Clearly he is far bolder in that regard than I am.

I found explaining the distinction of my role as a member of a community, who then came to study that community as an academic, somewhat problematic. At one point, I described myself as feeling like a “poacher turned gamekeeper” which seemed to resonate with most people.

The common difficulties seemed to be for academics to engage in a meaningful way with communities rather than going out to meet them with a hypothesis in mind, which they then needed “real” people to help them prove or disprove. On the flip side, communities were looking for meaningful ways to approach universities with real situations and concerns that would benefit from rigorous academic research.

We noted that for the communities involved with what they considered to be successful research projects, engagement with Higher Education institutions often seemed to be very dependent on who they knew or who they had worked with before. There was, however, a sense of real energy in the room, believing that, if we could overcome these divides, then really important and meaningful research could be undertaken which would benefit academia but also impact in real ways to make a difference for actual communities.

One example was highlighted by Brighton University who maintain a community-based approach to creating partnerships by providing a “help desk”. This provides a single point of contact for community groups, when approaching the university with pieces of work which they feel are important. It is then the responsibility of the help desk staff to match the group, if possible, with a suitable department or academic – effectively turning the more traditional process on its head.

The conference concluded that real public value from research was not about universities offering “quick evaluations or specialist inputs in exchange for communities offering access to a ‘real world’. Rather it is about creating substantive conversations between different sets of expertise and experience that university and community partners offer”.

I believe the Plymouth LGBT Archive has had meaning for both local and research communities due to the flexibility of roles when defining and working towards mutual beneficial outcomes. Attending this conference highlighted many other opportunities to create truly ‘living’ knowledge which I hope to explore in future.

About the Author:

Alan Butler has recently completed his AHRC-funded PhD, co-supervised by the School of Humanities & Performing Arts at Plymouth University and Plymouth City Council. As a co-director of Pride in Plymouth, he works closely with various statutory and voluntary bodies as well as with schools and employers in the Plymouth area. Alan also works with Plymouth University, as an Associate Lecturer, and the Plymouth School of Creative Arts. He is a member of the national committee of the Community Archive and Heritage Group.