BY JAMESON TUCKER

When I got into the office on Monday morning, I was happy (and a bit surprised) to find a box containing six copies of my book, The Construction of Reformed Identity in Jean Crespin’s Livre des Martyrs, which is coming out soon from Routledge.

This is based on my PhD thesis, which I did at the University of Warwick under the supervision of Penny Roberts, and is all about one of the most distinctive and influential genres of book from Europe’s Reformations: the martyrology or book of martyrs. Several parallel Protestant martyrologies were produced in the 1550s onwards, detailing the words and deeds of those who died for their faith, including a series of them printed in Geneva by the printer-publisher Jean Crespin (a refugee from Arras). These books were best-sellers in their time, and hugely influential in how we remember the Reformation, and in shaping national identity. The popular memory of Queen Mary Tudor as ‘Bloody Mary’, the Martyrs’ Memorials in Oxford, Exeter, Stratford, and elsewhere, owe a great deal to their figurative enshrinement by Foxe.

A growing amount of attention has been paid to these martyrologies in recent years: Brad Gregory published Salvation at Stake in 1999, comparing the martyrologies of Lutheran, Calvinist, Anglican, Anabaptist, and Catholic denominations. At the same time, The Acts and Monuments Online project was underway, a fifteen-year project to produce a reliable, detailed edition and commentary for the English martyrology, which also resulted in Evenden and Freeman’s study of the production of Foxe’s book.

As for myself, I was interested in early histories of the Reformation in Europe. I had used Jean Crespin’s French-language martyrology as a source for my MA, and knew that there was a lot that could be done with it. The Foxe project showed how the text of the Acts and Monuments changed over time, and given that a lot of the sources Foxe used have survived (and even some of his early proofs), historians have been able to show how the stories in it had been altered, corrected and adapted. For both Foxe and Crespin, these were important issues, because people (a good number in Crespin’s case) were learning the history and fundamentals of their religion from these books.

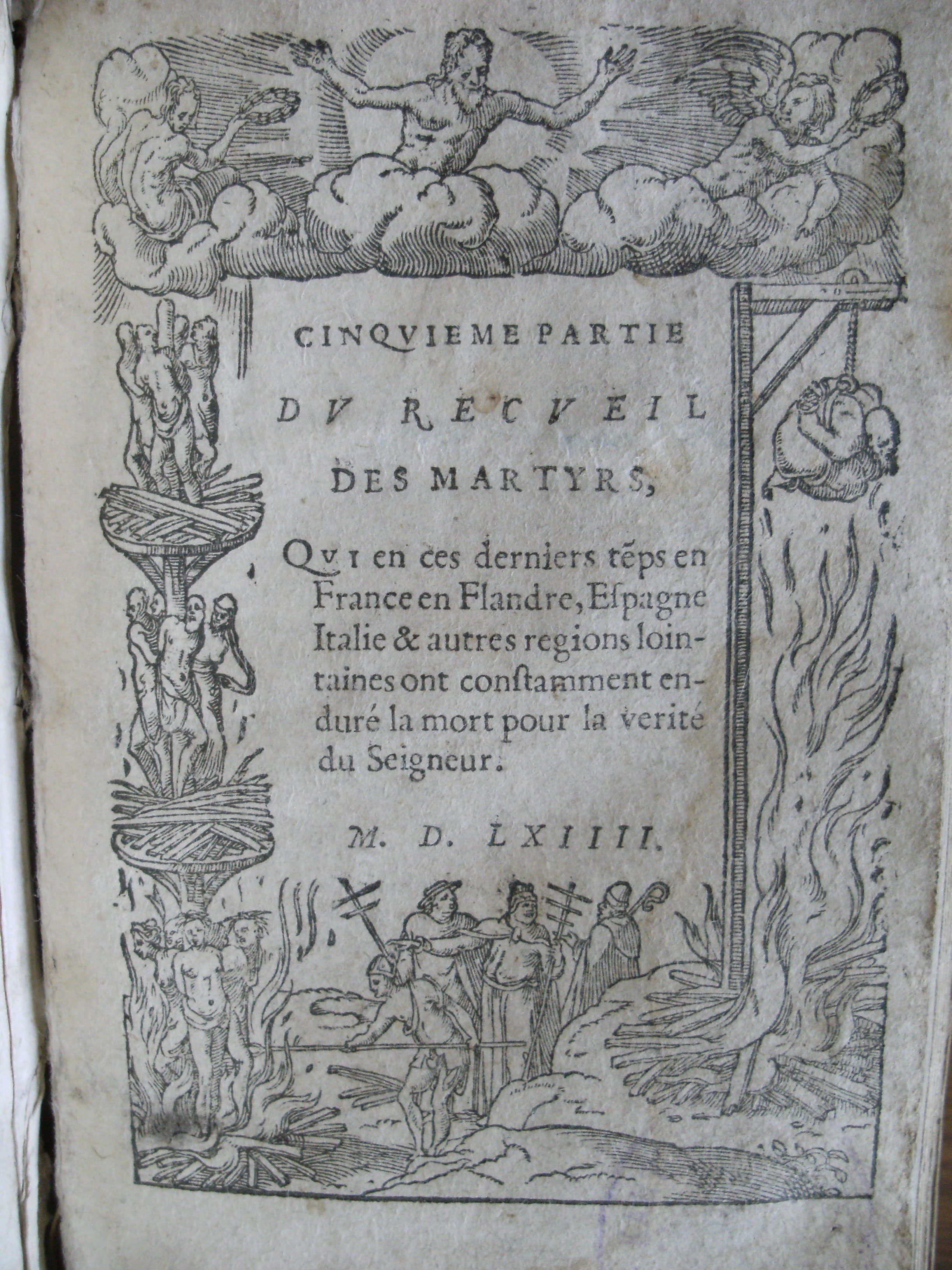

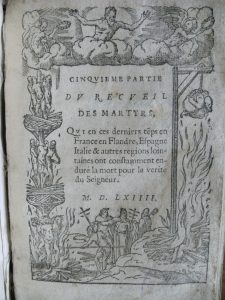

However, without the rather extraordinary survivals of Foxe’s sources, studying Crespin’s martyrology was going to be a challenge. Many of the martyrs had had the records of their trials burned with them, so there was no chance of comparing those with the printed versions. Crespin didn’t write very much himself at all, so it would be difficult to compare the content of the books (which he claimed were simply reproductions of letters and documents—an early primary source handbook!) with his own views and ideas. My idea was to compare all of the different versions of the book (in one form or another, there were seven in French, plus two in Latin produced between 1554 and 1570), and see where changes had been made over time. This was possible because the complicated production history had been studied in depth by Jean-Francois Gilmont, and there was at least one copy of each edition still surviving.

This sort of labour-intensive comparison was only really possible because of digital cameras and the like, because there was no ability to place two editions side-by-side. The only surviving copy of the fifth edition was in Solothurn, Switzerland, while the fourth edition only exists in Paris and Stuttgart. But I could compare each of them once I’d travelled about photographing busily. Some interesting points (I hope!) emerged.

In his 1550s editions, Crespin was happy to relay stories of the Peasants’ Wars in Germany, featuring a pastor executed in Lorraine shortly after the uprising was put down. In the context of the 1560s, and the wars in France (and the continued association of Huguenots with rebellon), these accounts started to disappear; by 1570, the only reference to the Peasants’ War was a new section on how it had led to the ‘Insanity of the Anabaptists’.

The confession of faith of the Vaudois, or Waldensians, from near Avignon, also saw dramatic changes between 1554 and 1564, as Crespin reduced it in size again and then replaced it until it was a safe, standard-issue, Calvinist statement. It may not have reflected the beliefs of the Vaudois, but a French Protestant reading it would not be led astray, and that was a key factor in Crespin’s thinking. As Andrew Pettegree has argued, these were books meant to educate as much as to inspire, and Crespin (who printed several books for Calvin himself) could not be spreading false doctrines.

And so this became one of my key arguments—that if we look closely at the changes in the text, we can get a good sense of what Crespin thought he was up, and that more than a history of the early Huguenot movement, this was an educational text. If you were to read the whole thing (and really, I can’t recommend that), you’d get a good working knowledge of what Calvinists thought about the Pope (bad), the Mass (bad), and state authority (complicated), and how they were meant to behave. Given the reach and influence of the Livre des martyrs, which we know was still widely read a century later; these can be important ideas to understand.

About the Author:

Dr Jameson Tucker is a lecturer in Early Modern History at the University of Plymouth. His research interests include early modern religion, identity and propaganda, particularly in relation to the French Reformation. His most recent book ‘All the True Christians: Strangers in the Martyrology of Jean Crespin‘, published by Routledge, is available now.

Dr Jameson Tucker is a lecturer in Early Modern History at the University of Plymouth. His research interests include early modern religion, identity and propaganda, particularly in relation to the French Reformation. His most recent book ‘All the True Christians: Strangers in the Martyrology of Jean Crespin‘, published by Routledge, is available now.