BY JAMES GREGORY

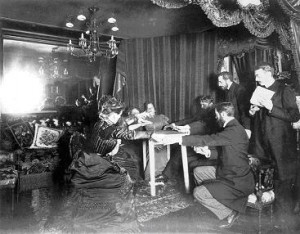

Devonport in the early 1870s. A former Baptist minister from Bristol leads meetings in the gas-lit parlour of a tradesman. The audience gather around an ordinary cloth-covered table. But the phenomena that they are there to experience will be decidedly out of the ordinary.

Over the next few years, members of various religious denominations will attend séances, prefacing their activities with prayer and finding, among other manifestations, that their hymns are accompanied by the table beating time with the tunes ‘in such a graceful and hearty manner that some [are] affected to tears’.

These Devonport and Plymouth spiritualists were enthusiastically reported in the late-Victorian national spiritualist press as pioneers: spreading the news of a new reformation to Exeter and Cornwall.

I have explored the late-Victorian spiritualist ‘crusade in the South West’ over recent years as part of ongoing research into Victorian ‘movements’. I first encountered the rich archive of journals such as the Medium and Daybreak while researching Victorian vegetarianism. The hard slog of going through the small print in physical copies is no longer required. The International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals provides a large online archive.

This digitised collection and the files of provincial newspapers such as the Devonport Independent and Western Daily Mercury, provide the basis for recreating the public and private activities of spiritualist societies in the provinces. With more to find out from the local newspapers in Plymouth and Exeter, I have started the work of identifying the leaders and rank-and-file membership of the spiritualist societies in Plymouth and Exeter.

The organised spiritualism of the South West was a late-Victorian development. But spiritualism had been widely discussed: earnestly by inquirers, anxiously by the religious orthodox (fearing satanic origins, for instance), and with amusement by those enjoying comic paragraphs on table-rapping, after it crossed the Atlantic from the United States about 1850.

As the movement gathered adherents, local activities and activists, organisations and venues across the country were reported in a national spiritualist press. While the newspapers of the South West covered national scandals of fraudulent spiritualists, and advertised entertainments that sought to reveal the tricks of mediums from the 1850s onwards, there were no signs of locally organised spiritualists until the 1870s.

The journal, The Spiritualist, stated in 1878:

While Spiritualism was spreading with rapidity in Lancashire, Yorkshire, and the North, it seemed utterly incompetent to take root in South-Western districts. Whatever the cause may have been, it is removed, so far as the beautiful county of Devon is concerned. We possess information that it has taken root in at least six Devonshire towns, and that in one of them mediums are multiplying.

The leading figure was a young Bible Christian minister, Charles Ware. His belief in spiritualism – established in April 1879 through meetings at the home of the local preacher Henry Pine (Crimean War veteran and army pensioner) at Devonport – led to his expulsion from the denomination.

As a result, Ware formed a Free Spiritual Society with members of his congregation. This met first in the front room of house at The Octagon – a prominent location – in Plymouth in March 1881. Soon services were conducted in a hall in Richmond Street with the aid of a harmonium. Another floating table (so Ware informed readers of Medium and Daybreak) kept time to the music.

Plymouth and Exeter spiritualists reflect the strong Protestant Nonconformity of the region rather than the ‘free thought’ or anti-Christian proclivities suggested by other scholars of spiritualism. Historians such as Joy Dixon have noted that women had opportunities for prominent roles as mediums and local leaders and the South West is no exception.

The sailor’s wife Sarah Martin Chapman, and Miss Bond of Stoke who developed abilities as a trance medium, were crucial in sustaining activities in a hostile or indifferent environment. Spiritualist funerals, spurning the conventions of sombre mourning, sporting symbolic white flowers, offering mediumistic messages by the grave, challenged conventions.

The mainstream press and spiritualist papers give glimpses of the strong feelings stimulated by spiritualist propaganda. Late-Victorian Exeter was notably rowdy in its reaction: hissing and laughing at the trance lecturer Mrs Groom of Birmingham in 1884 for her rejection of the belief in bodily resurrection.

Plymouth spiritualism involved some intriguing individuals: such as the working man, Mr Burt, who ploughed his own earnings into handbills and notices for the workers leaving Devonport Dockyard; the Quaker civil engineer and antiquarian Charles Dymond; and the aged wholesale stationer and former leader of Second Adventist Millerites, Edmund Micklewood. I hope to uncover more of the social background of the local spiritualists, in a provincial case study that locates them within the wider ‘ecology’ of late-Victorian religious, philanthropic or progressive organisations.

Those who studied spiritualism risked their reputations and even personal liberty. For instance, the incarceration in a lunatic asylum of Louisa Lowe, of Upottery near Honiton, led to her work as a lunacy law reformer. Alex Owen, who wrote about this famous case, quotes Lowe’s statement that a ‘Mrs.––– at Plymouth, and others, too numerous to name, have been and are constantly incarcerated for speaking of spiritual visions’. Ware lost his job as a local minister but felt that he had gained much more: ‘a new world of thought and experience’. It was he who spread the spiritualist cause to Exeter – embracing the challenges in a conservative cathedral city.

‘It was contrary to reason to believe that the limb of a soldier or sailor amputated in a foreign country could be joined again to the physical body after death,’ Mrs Groom had asserted in 1884. Uproar had been the Exonian response but after the mass slaughter of the Great War a new stimulus to spiritualism would be the comfort of contact with the spirits of physically annihilated loved ones.

The legacy of Victorian and post-war spiritualism is visible in the spiritualist churches existing in the South West today.

About the author:

Dr James R.T.E. Gregory is Programme Leader for the MA & ResM in History, and Lecturer in British History since 1800 at Plymouth University. He is the author of The Poetry and the Politics: Radical Reform in Victorian England (2014) and Victorians Against the Gallows: Capital Punishment and the Abolitionist Movement in Nineteenth Century Britain (2011).