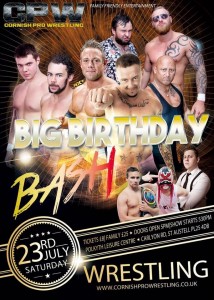

With a Cornish Pro Wrestling show coming up on Saturday, 23 July 2016, G.H. BENNETT offers a historian’s view of professional wrestling.

‘Wrestling – that’s fake, right?’ ‘Wrestling – that’s guys in tights or flowery briefs covered in body lotion, yes?’

Wrestling is usually, and swiftly, dismissed for a variety of reasons ranging from perceived artifice through to its violence. And yet professional wrestling in the United Kingdom continues to go from strength to strength with more promotions, more shows and steadily larger audiences. A sold out crowd for a show in Scotland, London or even in the South West can surpass the 1000 mark.

Almost exclusively drawn from blue collar ranks, audiences for shows are nevertheless remarkably diverse ranging from small children to those well past ‘four score years and ten’ – from builders, to mothers, to the disabled. The leading wrestling franchise WWE is a global media giant delivering televised wrestling 52 weeks of the year to 650 million homes in 25 languages.

Wrestling is a paradox: “a sport that isn’t a sport” and a cultural form enjoyed by millions that somehow doesn’t quite seem legitimate. It is this liminality, and the largely ephemeral nature of wrestling across decades of history, together with its inclusivity within the working class demographic, that gives it particular importance as a subject for academic study.

For a historian like myself, wrestling presents some significant challenges. Anyone can sit and analyse a wrestling show, but to go deeper into that world and behind the scenes is an involved process. The world of wrestling, perhaps in tribute to its nineteenth early twentieth century “carny” heritage, is not an open shop and to gain any sort of acceptance within that world involves signing up to a set of ethical standards which are as absolute as they are unwritten.

Wrestling is a shared experience that relies on trust that has to be earned (usually the hard way and over time). In writing this piece, and saying what I say, maintaining that trust remains of paramount importance.

That trust is further evident between wrestlers in the ring who rely on each other to tell a story through physical performance involving moves that are painful, dangerous and potentially deadly if mistimed, misdirected or improperly performed.

There is also the trust between performers and audience to produce a dialogue based on a suspension of disbelief. The audience has to want to believe in what they are seeing and the wrestlers must facilitate that by their performance and by their responsiveness to the audience.

The inner world of wrestling is protected by kayfabe (“carny” slang for “be fake” based on pig latin). Kayfabe is wrestling’s equivalent of the Cosa Nostra’s Omertà. To facilitate the suspension of disbelief under kayfabe storylines, identities and other elements vital to the performance are not revealed to the audience before, during or after the show.

Identities are frequently hidden behind in-ring wrestling names. Masks, particularly within Mexican wrestling create a further level of disguise. Take for example, the story of Sergio Gutiérrez Benítez a Catholic Priest in Mexico who enjoyed a 23 year career as a masked lucha libre wrestler as Fray Tormenta (Father Storm) to raise money for an orphanage.

The motivations and backgrounds of wrestlers vary considerably but there is invariably a strong emphasis on team, work ethic and responsiveness to fans. Most wrestlers demonstrate strong creative streaks to craft their characters, matches and storylines (together with entrance music, back stories and costume), along with outstanding emotional intelligence to work off each other, the promoter and the crowd before and during matches.

They enjoy a shared language and truly international wrestling culture which allows wrestlers who have not previously met to swiftly plan, rehearse and execute matches involving agreed moves and set pieces (spots).

This sense of sharing and, indeed, common values adds a further layer of intrinsic interest to wrestling. A wrestling match is an affirmation of shared cultural values: of the relationship between audience and wrestlers; of the hard work and training which allows performers to execute “spots” and to physically look the part; and of the human values which underpin a wrestling narrative.

At its simplest wrestling involves tales of good (“faces”) versus evil (“heels”). The basic narrative is firmly traditional (and wrestling has close associations with mediaeval miracle plays that can be documented as far back as 1300ad) but, in affirmation of the realities of life, good does not always win, justice is not always done and hard work and effort sometimes go unrewarded.

A sense of virtuous struggle against evil that does not play fair, or fate that is often cruel, can be found at the heart of most wrestling matches. What the majority of the audience wants to happen (the triumph of good over evil) is as fascinating and revealing as the performances which either deliver or go against that hope.

It may seem controversial or surprising to say it that there is a nebulous religiosity at play in the collective performance and spectacle of wrestling (often involving performances of suffering and ultimate redemption). Good is often thwarted if only to ramp up the sense of justice and achievement when it finally triumphs (perhaps after a lengthy rivalry) at the next match, at the next show.

An audience trusts that they live in a world in which good will ultimately win out. The desire to see that ultimate victory is what brings the audience to the next show. This is evident amongst professional wrestling audiences whether in the UK, the USA or Mexico.

In a UK context this apparent religiosity, and continuities from the early modern period, are striking and surprising, despite what might be described as a post religious society.

On top of this grounding, wrestling has value for the study of cultural history because of its engagement with contemporary popular culture. The use of entrance music from the 1980s onwards, wrestling characters (often drawing on archetypes and stereotypes, sometimes for comedic value), and features of particular matches (perhaps with references to current events, film or tv) anchor them firmly within the popular culture of a particular period.

The principle of engaging the audience means that wrestling works with, or consciously works against, social attitudes towards a range of issues from gender, to race, to religion, to domestic politics, to international relations.

A “heel” can attract “the heat” of the audience by challenging social convention, while a “face” may seek the support of the crowd by being seen as the embodiment of the social values of the majority. For example, the re-emergence of a muscular Russian foreign policy under Putin has seen the return of “Russian” characters as “heels” in professional wrestling.

A wrestling show is made by people: people from a sector of society whose lives, values and hopes have perhaps always been remote from the elite. It is performance at its most democratic with wrestling roster and audience collaborating in a live, improvised and reactive performance.

Wrestling offers historians a challenging way to read cultural history over the decades, and a place where we can realise the true value of interdisciplinary research in the arts.

About the Author:

Dr G.H. Bennett is Associate Professor (Reader) in History at Plymouth University. His many books include The Nazi,The Painter and the Forgotten Story of the SS Road (Reaktion, 2012), The RAF’s French Foreign Legion: De Gaulle, the British and the Re-Emergence of French Air Power 1940-45 (Continuum, 2011) and, with Gilbert S. Guinn, British Naval Aviation in World War II (IB Tauris, 2007; paperback 2012). He also works with the University of Plymouth Press and Britannia Naval College on a series of books dealing with the Naval History of the Second World War.