By ANN LYON and JAMES GREGORY

The political history of the British ‘long nineteenth-century’ is characterised by debates about the constitution in which parliamentary reform – the extension of the parliamentary franchise, the redrawing of constituencies, the power of the House of Lords, prominently figure. The judicial bench were recognised to have a political role too.

The judiciary, for instance, had a role in passing judgments that had political consequences – whether in relation to trade unions, or in matters of controversy relating to the established Church in England (where the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council passed various judgments, for instance on high church ritualism).

Source: Wikemedia Commons

Critics have waited for a more fulsome defence of the judiciary from Liz Truss, the first female Lord Chancellor. But if we go back over one hundred and eighty years, we have the figure of Lord Chancellor Henry Brougham heralded alongside Lord Grey as defenders of the Reform Bill in popular prints such as the broadside printed by Kiernan of Manchester in 1831, in the British Museum print collection.

And two decades later, from the perspective of Scotland – with its different legal system – we have the defence of judges in the Glasgow Gazette, in an editorial comment critical of the Whig-Liberal government’s proposed cuts:

We are for reduction and economy in every department of the State that can afford it but can never seek to prostrate the dignity and independence of our Supreme Judges — far less to rob them of their fixed salaries, on the faith of which they consented to wear the judicial ermine. It is to them: it is, we say, to these Judges, in eminent degree, more than to a base and servile Parliament, that we are indebted for the preservation of our rights and liberties…

Glasgow Gazette, 17 August 1850

Of course, judges had been unpopular in the recent past: viewed as a hostile body and part of ‘Old Corruption’, by late eighteenth-century radicals who contrasted the bench unfavourably with the jury as palladium of English liberty (on which see James Epstein’s essay ‘“Our real constitution”: trial defences and radical memory in the Age of Revolution’, in James Vernon, ed., Re-reading the constitution. New narrative in the political history of England’s long nineteenth century (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Some of the more violent responses to judges can be seen in the print collection of the British Museum, for instance George Cruikshank’s ‘The Portable Purificator of our Courts of Law & Equity being the Way our Great & Glorious Alfred cured the Winkings & Squintings of his Judges’ (1813), which shows a judge being hanged …

And consider the following comment, from Thomas Wooler, at a public meeting after the trial of the radical printer William Hone:

They all knew as a matter of history, that a measure was passed early in his present Majesty’s reign, which, as the name went, had for its object, making the Judges independent of the Crown. But it was a strange independence for these high characters, that the Crown should appoint them in the first instance; and that they should afterwards for life retain the same high salaries. From the Crown then they got everything—from the people nothing—and did not the regular march of judicial, like any other official patronage, shew the independent qualities for which Judges were selected by the Crown? Did the people not see it in the opinions invariably pronounced by Learned Judges in every case of libel which came under their cognizance?

Trial By Jury and Liberty of The Press. The Proceedings at The Public Meeting, December 29, 1817, at the City of London Tavern (London: Hone, 1818), pp.16-17

The role of the jury in defending even foreigners from tyranny is presented in the case of Dr Simon Bernard the republican, tried before a jury of twelve Englishmen in April 1858 in the aftermath of the Orsini plot, and discussed in Margot Finn’s After Chartism: Class and Nation in English Radical Politics 1848-1874 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Chartists of the early-Victorian era, faced with trials for rebellion and other acts of sedition, were as critical of the judicial bench as their radical forebears. The Northern Star published a poem, ‘The Judges are Going to Jail’ in February 1840, a response to the trial of Frost and the Newport Chartists. For ‘Publicola,’ in the Glasgow-published Chartist Circular, in January 1842:

Of all the corrupt servants of the public our Judges have been the worst, except the Bishops; but the Judges lay claim to purity, and the Bishops make no such pretensions. This is a vast difference. Our Judges have created as individuals all that is called Common Law, and much of this relates to the most important subjects, and is entirely subversive of the liberties of the people. In England it is almost impossible to remove a Judge, however tyrannical, stupid, ignorant, or even corrupt. Our slavish and dull Jurymen look upon a Judge as a demi-god, and, instead of checking their impudence, or resenting their want of honesty, or reproving their arbitrary conduct, and interference with the Jury-panel, our Jurymen succumb to the Bench as the veriest of slaves.

‘The Third President of America. Part II’, Chartist Circular, 1 January 1842, p.495.

Victorian judges came from the upper classes, their prejudices as expressd on the bench, in social and economic matters reflecting this background. In the sphere of labour relations, the trade unions were critical of judicial bias at the end of our period, thus one delegate at the Trade Union Congress in 1900 declared, ‘he could not trust the judges of this country to give a fair and impartial verdict on any question as to the conditions of labour which might be remitted to them’ (as quoted in Henry Pelling, Popular Politics & Society in Late Victorian Britain).

There is much to explore about the discourse around nineteenth-century judges in popular culture. Moments of tension around controversial judicial decisions (or reported comments) might stimulate, as now, debates about attacks on the ‘dignity and independence’ of the judiciary; and involve discussion within Parliament. These were not even merely constitutional matters.

For instance, there is the case of Baron George Bramwell on the North Wales circuit, impugning the Welsh in general, after the acquittal for embezzlement of David Williams, in Bala in 1859 – which understandably generated hostile comments in the Welsh press (see Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, 16 April 1859 and The Examiner, 16 April 1859 for the report of the exchange in the House of Commons between Enoch Salisbury, the MP for Chester and the Home Secretary, Thomas Sotheron Estcourt).

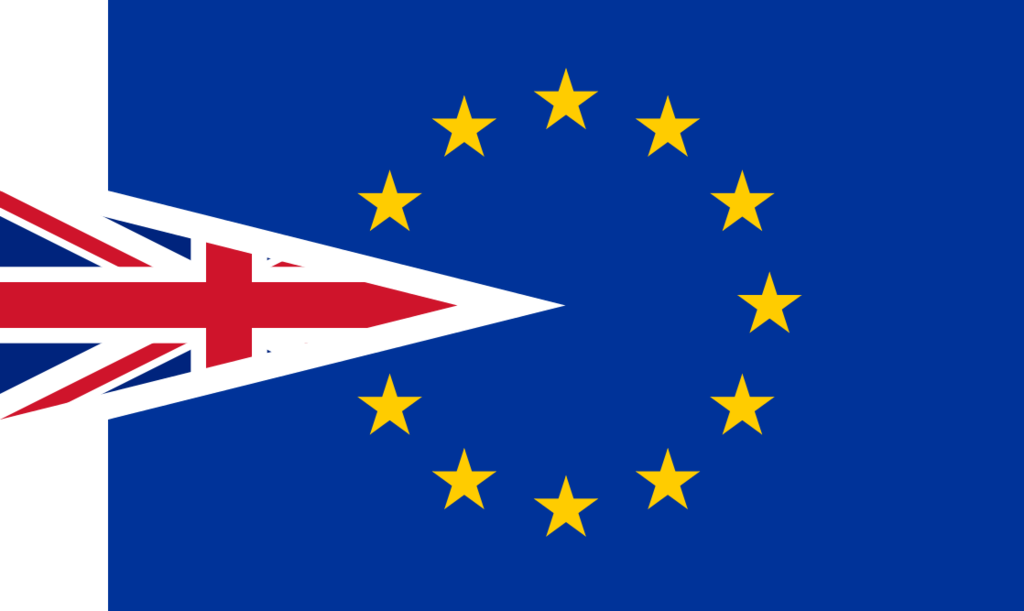

The decision of the Queen’s Bench Divisional Court in the case of R (on the application of Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union has attracted saturation coverage, and not a little ill-informed comment, since it was published on Thursday 3 November 2016. No doubt it will continue to do so, at any rate until the result of the Government’s appeal to the Supreme Court is known (some time in December).

Despite claims by some commentators that the judiciary are acting beyond their constitutional role, and seeking to frustrate democracy, in examining and ruling on the extent of executive power, the judges were here fulfilling a long-established role, in which they are frequently called upon to check the power of an executive which very largely controls Parliament.

The decision in Entick v Carrington in 1765 establishes that the British Government has no special powers merely because it is the Government, and that it must show positive legal authority for any acts which interfere with the existing rights of citizens. Mr Entick, a printer and associate of the radical MP John Wilkes, argued that a search of his house and the seizure of his papers, in the absence of such authority, amounted to trespass to his property, and the court agreed with him.

Entick v Carrington may be regarded as the beginning of judicial review, in which the High Court considers whether an executive body has acted within it powers and used those powers in a proper manner. In Miller, the applicants sought a declaration in judicial review as to whether, following the referendum majority in favour of leaving the European Union, the Government could lawfully begin the Article 50 process for withdrawal by exercise of the Royal Prerogative alone or whether authorisation by Parliament is necessary.

That is the legal issue in the case, but the waters are very much muddied by suspicion that hard-line Remainers are seeking to prevent withdrawal by reliance on legal technicalities.

About the authors:

Dr James R.T.E. Gregory is Programme Leader for the MA & ResM in History, and Lecturer in British History since 1800 at Plymouth University. He is the author of The Poetry and the Politics: Radical Reform in Victorian England (2014) and Victorians Against the Gallows: Capital Punishment and the Abolitionist Movement in Nineteenth Century Britain (2011).

Dr James R.T.E. Gregory is Programme Leader for the MA & ResM in History, and Lecturer in British History since 1800 at Plymouth University. He is the author of The Poetry and the Politics: Radical Reform in Victorian England (2014) and Victorians Against the Gallows: Capital Punishment and the Abolitionist Movement in Nineteenth Century Britain (2011).

Ann Lyon is a lecturer in Law in the School of Law, Criminology and Government at Plymouth University. Her research interests include Constitutional and Administrative Law, Military Law and Constitutional History. She is the author of Constitutional History of the UK (2007),