BY JAMES GREGORY

The recent international conference, ‘Union and Disunion in the Nineteenth Century’ held at the University of Plymouth (22 – 23 June 2017) looked at union and disunion from the level of families separated by mental health or poverty, through the local history of Union Street and the union of the three towns that became Plymouth in 1914; to the technological agents of union represented by steam-powered maritime transport; state-building systems of union such as postal service and currency; to moments of disunions from the ‘white’ mutiny after the Indian ‘rebellion’ of 1857; and the American Civil War (1861 – 1865), to European projects of union such as the Zollverein of German states after 1834. Papers brought us insights from the social circles of high diplomacy, from Lancastrian dialect poetry, and the evidence of Victorian novels and Georgian Gothic. Legal history and art history were represented.

* * * * *

In this blog, James Gregory briefly considers the discourse of union and disunion in early-nineteenth century British politics: noting how union was debated and represented in radicalism in the post-1815 ‘reform’ era of ‘political unions’ (such as, most famously, the ‘Birmingham Political Union’ led by Thomas Attwood), in trade union formation (including large-scale entities such as the ‘Grand National Consolidated Trade Union’ of 1834) and in the context of concerted anti-radical activities by a State and by political elites in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

Union wasn’t just debated and organised. In order to propagandise for and against, the idea of union was expressed iconographically. We might look for earlier representation of union and disunion in the eighteenth-century imagery of the American Revolution and parallels in the next century in the American Civil War: with lithographic and wood engraved images of serpents or hydras of disunion or secession (being strangled or clubbed by various infant or adult Hercules). These perhaps thematically originate in the famous image of the divided serpent, with the motto ‘JOIN, or DIE’ of 1754 – and the variant ‘UNITE or DIE’ – to encourage the union of colonies against changing enemies (see Lester C. Olson, Benjamin Franklin’s Vision of American Community: A Study in Rhetorical Iconology of 2004, ch.3).

The British iconography of union is to be found expressed in such obvious places as banners, and in satirical or non-satirical engravings of radical political gatherings (for example, the lithograph ‘The Gathering of the Unions on New Hall Hill Birmingham’ by Henry Harris, recording the meetings taking place in May 1832. Depictions of the gatherings at New Hall Hill show the detail of a banner with the legend, ‘Attwood and Union’ among other mottoes). Discussions of union as aspiration and necessity are to be found in texts as varied as the writings and utterances of the pioneer socialist, Robert Owen (1771 – 1858), and his followers (for whom union, combination and extensive social rearrangements were the goal), and in essays and comments in the broader radical press.

The statement ‘union was strength’ was often uttered in the nineteenth century, in many different contexts. Reflections in British radical literature on union were fundamentally about power: whether it was to be achieved through a combination by employers or by workers; whether union was in advance of the great social and economic principle of co-operation; or whether it was some effort at creating a mass platform such as the ‘one bond of brotherly love and unanimity’ that sought to bring together the radicals in ‘Orator’ Henry Hunt’s ‘Great Northern Radical Union’ (1821). This was actually designed to raise funds to get Hunt (1773 – 1835) elected as a MP (see the letter he penned, from ‘Ilchester Bastille,’ in his periodical To the Radical Reformers, Male and Female, of England, Ireland and Scotland, 24 September 1821, p.328). The aged Robert Owen would speak of the ‘Necessity of Union among the Leaders of Progress’ in 1850 (as reported in the freethinking journal, The Reasoner, 13 February 1850, p.51).

Working-class political strength was to be manifest through ‘grand’ and ‘firm’ unions. We might think especially of the role of trade unions. The literature of trade unionism, not surprisingly, was saturated with references to union, as it advocated ‘workmen uniting for the purpose of mutual self-protection on the subject of wages’ (the definition from ‘Trade Unions – Part First, The Co-operator, 1829).

The explicitly political unions established in the post-war period included various ‘Union Clubs’ formed for parliamentary reforms such as annual parliaments and universal (male) suffrage), whose activities had frightened parliamentarians in 1817. There was that famous body which was led by the currency reformer Thomas Attwood during the Great Reform Act crisis. The ‘General Political Union,’ for redressing ‘public wrongs and grievances’ was established after a meeting in Beardsworth Repository in Birmingham in 25 January 1830.

The iconography of political union in this period drew on a common symbolic repertoire: including the fasces, that familiar emblem of strength through union in the twentieth century – thus a ‘bundle of oak sticks, emblematical of union and strength, was borne on an oak staff before the bearers of the Bristol Petition,’ in 1817 (see Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, 16 August 1817, p.620). One cartoon of 1832, stimulated by the parliamentary reform crisis, and entitled ‘The Union of the Scotch Greys at Birmingham,’ printed in The Chronologist (and published by J. Lewis Marks in London: a copy can be seen via the online collection of the British Museum,1868,0808.13367) represents a serpent of corruption coiling around the fasces and cap of liberty while a mounted soldier, representing the supposedly sympathetic Greys, shakes hands with a member of the Birmingham Political Union, their union shown by their hands shaking (with a cloth labelled ‘UNION’ wrapped around their arms). In 1832 in an engraving by Josiah Allen, W. Green and Scriven, the banker and reformer Thomas Attwood (1783 – 1856) is depicted in one elaborate engraving with a bundle of rods joined by ribbons with the legend ‘unity, liberty and prosperity’, and elsewhere he is shown holding a scroll emblazoned with the word ‘Union,’ in a wood engraving in one newspaper. A commemorative medal struck for the Birmingham Political Union in 1830 had a dove atop a fasces bundle, with an olive of peace, under the motto: ‘unity liberty, prosperity’.

Our conference keynote speaker Gordon Pentland, has explored, in his study The Spirit of the Union: Popular Politics in Scotland, published in 2011, the symbolism of fasces in radical constitutionalism: in the town of Lewes in Sussex there was even a ‘Bundle of Sticks Society’ formed by local Whigs in 1818 which used the iconography. If the argument for combined strength drew on fables such as Aesop’s bundle of sticks, that detail of hands being shaken, grasped or held, can be seen in many artefacts to do with union: appearing in trade union banners for example (see Annie Ravenhill-Johnson’s The Art and Ideology of the Trade Union Emblem, 1850–1925 published in 2013, p.32, on the symbol of the hands, and on the general topic). In my conference paper, looking at the diplomatic ramifications of the English holiday visit to Paris organized in April 1849, I showed several designs of commemorative medals struck in Paris, displaying the hands clasped in unity. The conference had an accompanying exhibition which showed the symbolic gesture appearing in a range of artefacts from pledge cards for the late-Victorian Gospel Temperance Union, up to the iconography of Marianne and Britannia holding hands for the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908 and the socialist Walter Crane’s design for workers of the world uniting .

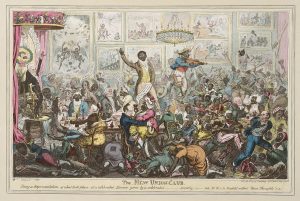

The early-nineteenth century critics of radicals were fearful of radical combination. A writer in the periodical Anti-Jacobin Review and Protestant Advocate in 1820 saw ‘Union societies’ as a ‘favourite plan with the advocates of radicalism’ (vol. LVIII, March–August 1820, p.187). The cartoon by the leading cartoonist of the age (and contributor to the Anti-Jacobin), James Gillray (1756 – 1815), ‘The Union Club’ (published in 1801: a copy can be seen via the online collection of the British Museum, 1868,0808.6922), had its satirical comment:

Thus we’ll Join Heads & Hands all discord shall cease,

And with Bottles & Glasses the Union increase.

As Patriots of England we’ll drink down the Sun

And to dear Friends in Ireland we’ll drink down the Moon

(Gillray’s famous image was later emulated by George Cruikshank’s racist ‘The New Union: Club, Being a Representation of what took place at a celebrated Dinner, given by a celebrated ––society,’ published 19 July 1819: a copy can also be seen via the online collection of the British Museum,1859,0316.148

‘Union is strength in all cases and without any exception,’ asserted the Owenite socialist author of ‘Considerations’ for those who wish to untie under the New System of Union and Mutual Co-operation (reprinted in Gregory Claeys, Owenite Socialism: 1823–1831, published in 2005). In Owenism, not only was the social system to be one of mutual co-operation, with the ‘principle of union’ (see Owen’s ‘Report to the County of Lanark’ of 1820; and his autobiographical The Life of Robert Owen) rather than a social system established on the basis of individualism, but we see the call for union in thought too, as the reverse of the diversity of opinion about religious beliefs in the old moral world. Universal facts were to be opposed to the ‘jarring opinions upon abstract subjects,’ in the words of Thomas Macconnell in 1832 (The Signs of the Times. A Lecture Delivered in … Robert Owen’s Institution, Etc (London: Eamonson, 1832), p.13), and the ‘advantages of union in practice’ were extolled. The Owenite future was concerned with the ‘practice of union’, and contrasted present-day division with the hoped-for ‘cordial union of interests’. And Owenite writers identified it in many other ideal forms (including the ‘free unions’ of the sexes), when they employed the language of union. But in order to make any union ‘consistent,’ in co-operative societies, so the Unitarian Reverend Franklin Baker argued in 1830, these needed to be formed from ‘equality’ of social condition and experience by restricting membership to the working classes. (See the Reverend F. Baker, ‘The Universal Pamphleteer. The Second Lecture on Co-operation. Delivered by the Reverend F. Baker, May 3, 1830, At the Sessions’ Room, Bolton’ and also republished in Claeys, Owenite Socialism: 1823–1831).

Union requires an antithetical language of division and disunion, of competition and individuality. The exponents of union in radical politics identified weaknesses brought about by radical disunity, of working-class division, isolation and disorganization. Numerous were the essays in which radical politicians complained about the faulty basis for enlarged union; or the splits within radicalism and the failure to unite ‘the people’. Richard Carlile (1790 – 1843) reflected on this, in his essay, ‘To the Republicans of the Island of Great Britain’, published in the six-penny paper The Republican, 7 and 14 June 1822, from his cell in Dorchester Gaol: reflecting on ‘Union among Reformers’: ‘Union upon sound principles is my motto’ (The Republican, 1 March 1822, p.287).

Some found the reasons for mid-century radical disunion in leadership:

Each and all preach union, declare it to be the prime essential of success, make it the exordium and the climax of their speeches, and then go to their closets and sow discord broad cast

(‘The Political Reviewer. I. Politics and Socialism’, The Freethinker’s Magazine and Review of Theology, Politics, 1851, p.199.)

If there was more space here, it would be interesting to look at how the language of union appears in the journalism of the mass working-class Chartist movement. In the latter phase of Chartism, the leader George Julian Harney (1817 – 1890), writing in The Democratic Review, argued:

The first and most important step to be taken is, that we should become thoroughly united. We may behold in that talismanic word – Union! The lever by which the sons of labour may acquire the gigantic strength which will raise them to their legitimate position in the social scale.

(To the Trades of Great Britain and Ireland’, in The Democratic Review, June 1849, p.7)

Efforts to unite the democratic and socialist reformers were repeated on several occasions in the era of Chartism, with a latter-day effort in the ‘National Charter and Social Reform Union’ in October 1850. But read this splendid denunciation of the political failure to unite these parties, again from the pen of Harney, disillusioned:

We knew that ‘leaders’, one and all, had preached ‘union’ from the platform and through the press, and we believed them! We had heard them deplore the evils of disunion, and the foolishness of sectional agitation; we had heard them tell the people, times without number, that the disunion of the millions was the principal reason why they continued slaves; and we were foolish enough to believe that these men were in earnest in their appeals for ‘union.’ Hence the hope we cherished that a brighter day was about to dawn, that the ‘leaders’ were ready to sacrifice their jealousies and hatreds on the altar of the public good. We were deceived. The majority of these union preachers held aloof, some to see if the projected union would succeed before they patronised it; others to see if the Conference would commit itself to measures which would afford a pretext for patriotic denunciation.

(The Red Republican and the Friend of the People, 16 November 1850, p.173.)

Forging union, as political leaders in contemporary national politics know well, requires constant attention, with tangible rewards offered rather than merely rhetorical and symbolic gestures.

About the Author

Dr James R.T.E. Gregory is Programme Leader for the MA & ResM in History, and Lecturer in British History since 1800 at Plymouth University. He is the author of The Poetry and the Politics: Radical Reform in Victorian England (2014) and Victorians Against the Gallows: Capital Punishment and the Abolitionist Movement in Nineteenth Century Britain (2011).

Dr James R.T.E. Gregory is Programme Leader for the MA & ResM in History, and Lecturer in British History since 1800 at Plymouth University. He is the author of The Poetry and the Politics: Radical Reform in Victorian England (2014) and Victorians Against the Gallows: Capital Punishment and the Abolitionist Movement in Nineteenth Century Britain (2011).