Gemma Blackshaw, Professor of Art History, writes:

More than any other image, the self-portrait declares the artist as the subject of the work of art, and the work of art as the means by which we might know him (my use of the masculine pronoun is deliberate here), in all his creative, spiritual and sexual torment. Self-portraiture as a genre flourished during the modern period, the era which gave us Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch and of course, Egon Schiele, and this went hand in hand with the reinvigoration of the relations between art, madness and masculinity that art history as a discipline has always revered, but no more so than during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The myth of the mad artist, that uniquely anguished genius, has been roundly critiqued by feminist art historians in the scholarship on modernism in particular and yet it continues to be enshrined in the monograph – the study of the single artist’s ‘life and work’ – the monographic exhibition, and the plethora of novels, films, and television documentaries that, in their different forms and modes of address, all go in search of the same, inextricably linked questions: who was this man, and what made him so extraordinary?

Biographical material can make the pursuit of these questions all the more compelling and on this, Schiele – along with his immediate precursors van Gogh and Munch, artists he much admired – does not disappoint. Born into the generation of a family which suffered from the effects of congenital syphilis; cast out by an uncle-benefactor following a defiant departure from the conservative Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (which had, nevertheless, introduced the young artist to life-drawing); sustained by the production of sexually explicit drawings of girls and young women, many of which included depictions of his own naked self; imprisoned for offenses against public morality and modesty; dead at the tender age of twenty-eight in the influenza epidemic of 1918, along with his wife, pregnant with their first child – the collapsing of life into work and work into life has proven hard to resist when thinking and writing about Schiele. The irony is that in the process of resisting it, as I have done in my own work over a number of years, new facets of the artist’s relationships, preoccupations and motivations have been revealed that concern those very same relations between art, madness and masculinity that remain so central to the literature on modern art.

In 2003, I embarked upon a four-year project, led by architectural historian Leslie Topp, which sought to chart the multiple and multifarious connections between psychiatry and the visual arts in Vienna and the wider Habsburg Empire from 1890 to 1914, the years associated with the city’s modernism. In our research, we discovered the extent to which mental illness and psychiatry resonated with Vienna’s modernist artists as they searched for new ways of representing their faces and bodies, for new terms to describe their practice, and for new articulations of their identities as ‘expressionists’. This was not a one-way street, moreover: we also uncovered the psychiatric profession’s interest in modernist architects and designers who were commissioned to create state psychiatric hospitals and private sanatoria for what were termed ‘nervous ailments’ as total works of art, their aesthetic reinforcing what the profession wanted to proclaim about its progressive, enlightened approaches to psychiatric treatment. What fascinated and continues to preoccupy me, however, is the ways in which Vienna’s modernist artists often critiqued such approaches, challenging the authority of the clinical psychiatry they were invested in through their figurative art – portraits and depictions of the naked human body which offered their own version of the ‘truth’ of the individual in extremis. ‘Vienna 1900’ was, then, a time and place in which psychiatrists, visual art practitioners and patients encountered and engaged with each other, often purposefully seeking each other out, and the resultant interactions were complex.

Schiele was implicated in this through his friendship with Adolf Kronfeld, a doctor who collected his work, and Erwin Osen, another artist who shared Kronfeld’s interest in what was commonly known at the time as ‘pathological expression’. In 1913, when the two men were sharing a studio space, Osen wrote to Schiele to say, ‘I still have to finish a portrait in Vienna and a few drawings at Steinhof for the “Science Day” where Dr. Kronfeld will be speaking on pathological expression in portraiture… I am already simulating all diseases so that I may get away sooner.’ Dr. Kronfeld had commissioned Osen to draw patients held in the Lower Austrian Provincial Institution for the Cure and Care of the Mentally and Nervously Ill ‘am Steinhof’, Vienna’s vast psychiatric hospital, designed by the modernist architect Otto Wagner and conceived by psychiatrists, government officials and awe-stuck visitors as a utopian city shining down on Vienna, which had opened to great acclaim in 1907. Guest speakers were invited to give public lectures at Steinhof; Dr. Kronfeld, we presume, used Osen’s drawings of patients to illustrate to his audience arguments that were being made by psychiatrists across Europe about how we might interpret the signifiers of disease they discerned in the patient’s head, face and body, their expressions, gestures and postures. This was, of course, the period in which Sigmund Freud, Vienna’s most renowned individual, was developing the practice of psychoanalysis, but mainstream psychiatry in the modern period preferred to engage with the certainties of the body than the ambiguities of the mind; this lies behind its appeal to artists committed to figuration.

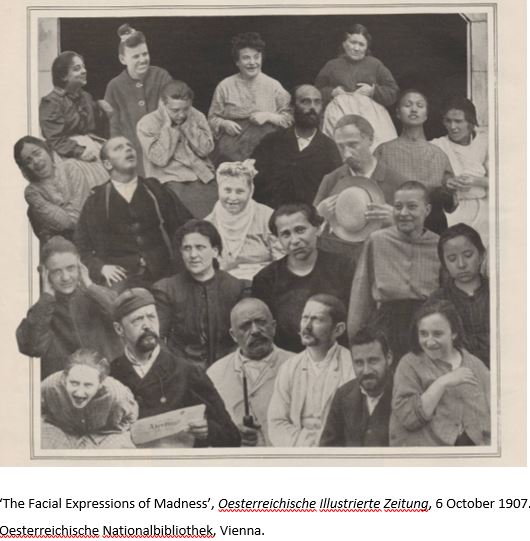

Photography played an important role in the popular dissemination of the image of mental and other forms of pathology, as seen in the astonishing collage ‘The Facial Expressions of Madness’, which included photographs of patients diagnosed with delusional disorders from asylums across Lower Austria, which was published in the Austrian Illustrated Newspaper alongside an article about Steinhof, in 1907. As the journalist remarked on his visit to the secure ward for mentally disturbed patients at Steinhof, ‘In endless variations, all the passions, all possible shades of feeling are shown in the faces of these unhappy people…’ Photographers were not the only professionals involved in the representation of such subjects; artists were also employed. Drawing, as Osen did, from life, artists’ images were considered to capture something more elusive about the patient, a mood that escaped the objectifying regard of the camera, which conveyed the ‘truth’ of their internal suffering in ways that could, on occasion, and at their most interesting, compromise the authority of the commissioning medical institution. We discovered three of Osen’s drawings, complete with notes which enabled us to identify the individuals he had portrayed, in a bank vault in Schladming, a winter-sports resort in the Austrian state of Styria. A handful of art historians had wondered about the impact of photographs of the insane on Schiele’s self-portraiture, noting his marked interest in the expressive potential of the facial grimace and bodily contortion that comprised the very subject of such imagery. Osen’s drawings, which we connected to notes in Schiele’s sketchbooks from the same period which refer to his own meetings with Dr. Kronfeld, enabled us to prove for the first time in the scholarship that Schiele’s life and work were entangled with those who studied the faces and bodies of ‘the mad’.

It would be fair to say that there was a degree of resistance to our foregrounding of these findings. Schiele’s break-through in 1910 to what might be described as a pathological aesthetic, characterised by the despairing face and distorted body, coincided with his most intense period of collaboration with Osen, who served as his life model throughout the same year. To acknowledge the modernist master’s debt to a lesser-known artist, however, and to place the modernist work in the context of visual culture – psychiatric or otherwise – is to challenge the values and hierarchies of the modernist art history that first brought Schiele to our attention, which emphasised the exceptionality of his life through narratives of angst, isolation, even madness itself. In his article reflecting on his visit to Steinhof in 1907, the journalist relayed a question he had heard from a patient addressing a visitor who wanted to take their photograph: ‘Tell me, do I look crazier than I am, or am I crazier than I look?’ Schiele’s self-portraits are so fascinating because this is the question they ask of us. The answer, to my mind, lies not within the discourse of art, madness and masculinity which characterises modernist art history, but in the pursuit of the embodied experiences of the patients who inspired the artist it so reveres.

***

This article was commissioned by Tate Etc. to accompany the exhibition Life in Motion: Egon Schiele / Francesca Woodman at Tate Liverpool from 24 May to 23 September 2018. It was published in issue 43 of the magazine, Summer 2018 (http://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc).

***

Dr Gemma Blackshaw is Professor of Art History at the University of Plymouth. She co-curated with Dr Leslie Topp (Birkbeck, University of London) the critically-acclaimed exhibition Madness and Modernity: Mental Illness and the Visual Arts in Vienna 1900 (Wellcome Collection, London, 2009). She is currently writing a book on the intersections of modernist figuration in Vienna with medicine’s contemporaneous visual, institutional, and therapeutic regimes.