Red Hot Mama: The Life of Sophie Tucker. By Lauren Rebecca Sklaroff. University of Texas Press, 2018. 275 pp., ISBN 978-4773-1236-0 (hc).

reviewed by Roberta Mock

Sophie Tucker was an entertainer. It’s not a term we use much anymore. We now tend to use words like celebrity – and she was certainly that too. In 1963, for instance, Paul McCartney introduced the Beatles’ cover of “Til There Was You” on the Royal Variety Performance by joking that it had already been recorded by their “favourite American group, Sophie Tucker”.

Tucker herself had cemented her iconic status as an outsized show biz trouper on the same programme the previous year, when she half-sang/half-recited her carefully constructed star text. Wearing a fur stole and glittery well-fitted evening dress, with coiffed blond hair and trademark chiffon scarf fluttering in hand, the “saga” she performed to the Queen and Prince Philip (and British television audiences watching at home) begins with her flinging “fishes and knishes” in her mother’s café while singing to any “mamzer” she thought would proffer a tip. Soon she ends up on Delancey Street in New York, where “to my surprise / I found there were guys / who idolize / gals oversize”.

This appears to be some strategic Jewish myth consolidation. As Lauren Rebecca Sklaroff notes in her new biography, Red Hot Mama, Tucker chose not to live with her Jewish relatives in the city, opting instead for a “dingy hotel” on Forty-Second Street, closer to Tin Pan Alley where she first set out to peddle her talents, armed with only a bucket load of chutzpah and Willie Howard’s calling card as an introduction (30-31).

It was in the same city, in 1953, that the Jewish Theatrical Guild sponsored a “golden jubilee” to celebrate Tucker’s fifty years in show business – although, in fact, her professional career began in 1906, when she escaped Hartford, Connecticut, to pursue dreams of stardom, leaving behind her baby son, Bert (the latter prudently left out of the narrative she presented in her Royal Variety turn, although discussed openly in her autobiography, Some of these Days, published in 1945). She used her own nostalgic speech on the occasion to honour the lost world of vaudeville in which she and her contemporaries found voices and flourished, a generation of Jewish immigrant artists that included Eddie Cantor, Irving Berlin, Al Jolson, Belle Baker and Fanny Brice.

While Tucker never managed a lasting romantic relationship, she told the assembled crowd that this was compensated by the “tender esteem” and love of her audiences (192); those audiences might also have surmised that all the sizzling sex to which she’d been referring in her performing persona as the “Last of the Red Hot Mamas” since the mid-1920s acted as some form of compensation as well. 1500 people attended this event, filling the Waldorf Astoria to capacity and raising money for seven charities that had been chosen by Tucker. The Yiddish Day-Jewish Journal that day published a piece emphasising her altruism (191); since the end of the second world war, Tucker had increasingly (although never exclusively) supported American Jewish congregations, benevolent societies and Zionist organisations.

Among the speakers offering tributes at her golden jubilee, the comedian Milton Berle proclaimed that “Sophie Tucker is to show business what Eleanor Roosevelt is to politics” (190). Sklaroff doesn’t really help us to unravel this assertion, although her book, in general, speaks around it. Presumably Berle meant that Tucker was a highly visible, passionate and compassionate woman – one perceived to be accomplished and authoritative – who was able to work around and through male-dominated power structures.

Like Roosevelt (who first opposed and then avoided endorsing the Equal Rights Amendment), it is difficult to firmly identify Tucker retrospectively as a feminist despite her own fierce independence and support for other women artists; in at least one interview, she stated that women should not try to “wear the pants” at home (187). Like Roosevelt, Tucker was committed to social justice and yet she was hesitant to speak publicly in support of the civil rights movement until the end of her life.

Sklaroff struggles, often apologetically, with the paradoxes inherent in Tucker’s career. These include the fact that the woman who presented as everybody’s Yiddishe mama was a pretty poor mother to her own son and, moreover, that this shmaltzy, selfless maternal figure was simultaneously a racy, selfish sexpot; that she celebrated body positive autonomy while making self-deprecating wisecracks; and, in particular, that (like many other Jewish performers on the vaudeville circuit) she first gained recognition as a “coon shouter” in blackface and profited by what we might now call cultural appropriation (although Sklaroff does not use that term herself). Tucker may have been occasionally performing in blackface as late as 1911 and was still uncomfortably singing “darky lullabys” in 1919 (91), a decade after she first appeared onstage (in her own words) “without some sort of disguise” (48).

Indeed, if there is a thematic thread in Sklaroff’s biography, it is that throughout her career, Tucker collaborated respectfully with black entertainers, using her privilege to provide opportunities and increased rights in the industry, and insisting on their receipt of due credit and acknowledgement. In a 1953 article in Ebony, Tucker discussed her indebtedness as a performer to African Americans and suggested that all “popular music” features a “Negro tinge” (189). Two years earlier, she had appeared on the cover of the same magazine with Josephine Baker, after introducing Baker’s first performance for an integrated audience in America at the Copa City nightclub in Miami: “Well if they come to blow up the place they’ll blow me up,” Tucker is quoted as announcing (183).

The main purpose of Sklaroff’s biography of Tucker is to restore her to “our cultural memory” (8). There are diverse intersecting reasons for her “seeming erasure”, not least, as Sklaroff notes, that far less critical attention has been paid to women in the canonisation of 20th century entertainment figures. Perhaps if Broadway Melody of 1938 (dir. Roy Del Ruth, 1937) – in which Tucker played the mother of then-unknown Judy Garland – hadn’t been quite so trite and fewer of Tucker’s scenes had ended up on the cutting room floor, Hollywood would have recognised the power of a gutsy middle-aged woman on screen.

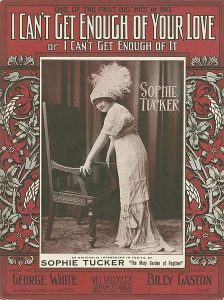

Perhaps if the 1962 musical based on Tucker’s life by the comedian Steve Allen hadn’t bombed, she would be remembered like Fanny Brice is today through her representation in Funny Girl. Perhaps if she had recorded both more of her massive repertoire, as well as more frequently, especially in the early years, more of her work would have circulated in the public domain before her memory faded. Tucker made her first recordings, “That Lovin’ Rag” and “My Husband’s in the City”, with Edison Records in 1910 and enjoyed considerable success with them (68), but she didn’t like the way her voice sounded on record and, like many vaudeville performers, she was wary of fixing and foreclosing upon material that remained in her repertoire as a touring artist.

This, for me, points to why Tucker is largely forgotten today: her success was based on her professional technique, her ability to mould “her act in sync with audience responses” (68), and her remarkable presence as a live performer. Ironically, this is also precisely why she is so important and should be remembered. Unfortunately, this represents the lacuna in Sklaroff’s biography, which features almost no description or analysis of Tucker’s performances, no attempt to help readers at historical distance understand just why this woman knocked ’em dead, night after night, year after year.

And while Sklaroff is probably too keen in her attempt to establish Tucker’s impact on almost every feisty woman performer one can name (from Julia Louis-Dreyfus to Miley Cyrus), she is also incorrect to state that Tucker’s “work was not sampled or reinvented by later artists” (8). Tucker directly and explicitly influenced a generation of bawdy female Jewish musical comedy performers including Pearl Williams, Belle Barth and Rusty Warren, whose work collectively lived on through drag and homage.

Most famously, via queer culture in the mid-1970s, Bette Midler began inserting “Sophie Tucker jokes” into her cabaret act; in one of several apparent misreadings in her book, Sklaroff seems to attribute these to Tucker herself (they were not, and as the jokes became progressively filthier, Midler stopped referring to her character as “Sophie Tucker”, abbreviating the name to simply “Soph”).

It is clear that Sklaroff worked closely and rigorously with Tucker’s personal archive – that is, the four hundred scrapbooks filled with programmes, cards, sheet music and newspaper clippings that Tucker assiduously compiled from 1907 until her death in 1966. The result is a well-intentioned life narrative that feels curiously external – one that rehearses an extended public performance without ever illuminating its root cause as a phenomenon – and is never quite able to reach inside its extraordinary subject.

Roberta Mock is Professor of Performance Studies and Director of the Doctoral College at the University of Plymouth. She is the author of Jewish Women on Stage, Film and Television and the Chair of the Theatre & Performance Research Association (TaPRA).