The whole notion of a Sustainable Earth Institute is likely to ruffle feathers. What does that mean – a ‘sustainable Earth’? After all, our planet has been practicing sustainability for four and a half billion years now. It is a survivor of unceasing physical and chemical change and traumatic biological turnover. The planet, it’s pretty clear, doesn’t have a problem. As the American comedian George Carlin put it…

‘The planet has been through a lot worse than us. Been through earthquakes, volcanoes, plate tectonics, continental drift, solar flares, sun spots, magnetic storms, the magnetic reversal of the poles … hundreds of thousands of years of bombardment by comets and asteroids and meteors, worldwide floods, tidal waves, worldwide fires, erosion, cosmic rays, recurring ice ages … And we think some plastic bags and some aluminum cans are going to make a difference? The planet isn’t going anywhere. WE are!

We’re going away. Pack your s**t, folks. We’re going away. And we won’t leave much of a trace, either. Maybe a little Styrofoam … The planet’ll be here and we’ll be long gone. Just another failed mutation. Just another closed-end biological mistake. An evolutionary cul-de-sac. The planet’ll shake us off like a bad case of fleas.’

Despite the indelicate expression, Carlin’s point has the benefit of clarity. The looming climatic and environmental threat is to us. To the sprawling, complex world that we have created. To the human planet. And, ultimately, to the human species.

For as long as we have been contemplating the world around us, our critical dependence on the natural diversity that surrounds us and underlies us has been obvious. The opening remarks of first great work about the planet – James Hutton’s ‘Theory of the Earth’ in 1788 – proclaim…

‘This globe of the earth is a habitable world, and on its fitness for this purpose, our sense of wisdom in its formation must depend’

Hutton’s opus magnus gave birth to the science of Geology – the study of the planet’s past, how it works and what that means for us. But his grand theory owes more to his early days as a medical student at Edinburgh University. Hutton wrote his thesis on the emerging notion of blood circulation – a constant cycle by which the body was renewed and replenished.

But Hutton got distracted easily, by rocks, by chemistry, by learning Chinese, by drink, and by the ladies. It was the result of one unfortunate romantic encounter with one woman that led his banishment from his beloved Edinburgh, dispatched by his furious father to the family’s run-down farm in the Scottish Borders.

Having resigned himself to a life of farming, Hutton decided to become good at it. He travelled down to Norfolk to research the most up to date new techniques of the English agricultural revolution. He hired a Suffolk plough and man and put them to work on his land. He introduced scientific crop rotations, boosted the fertility of the soil and soon his neaps and tatties and barley were flourishing. Hutton worked hard to increase the vitality of this soil. And he worked hard to look after it.

The only trouble was he was losing land to the Scottish downpours – and his precious farmland was getting washed away. This erosion of the land started to get Hutton seriously worried. If soil is continually washed out to sea surely eventually we’ll run out. And if we have no soil to grow our crops in, we starve.

Languishing in the back country, Hutton had plenty of time to think – and ponder this grim fate that would face the Earth if there was no means by which new land could be created. But being deeply religious, it made no sense that God would let his people starve. Hutton was convinced that the planet must have some way of creating new land.

The answer would come from a friend living on the other side of the country. James Watt was born in Greenock on the Clyde and by the time he met the other James, he was an engineer and an accomplished inventor. The improvements Watt made to the steam engine of the time allowed the critical harnessing of heat that would power the industrial revolution.

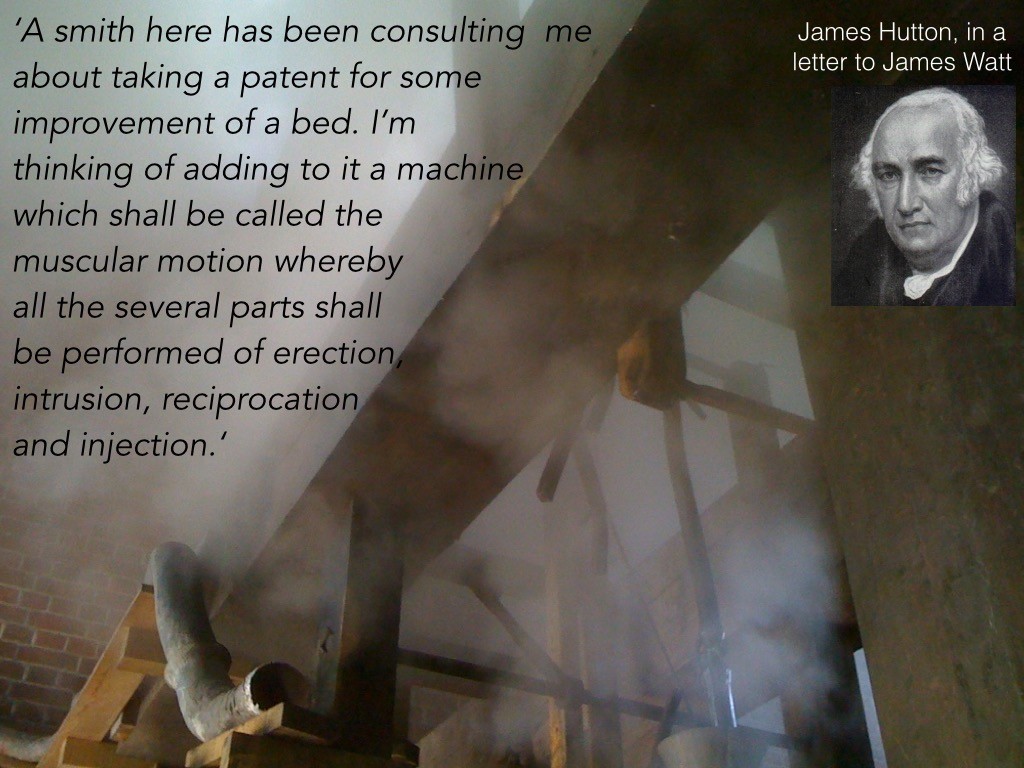

Hutton always had a thing for machines and he became fascinated with the new steam-powered contraptions of Watt. His interest, it seems, was always more than just theoretical. In one letter to James Watt, Hutton notes…

James Hutton, the staid, respected grandaddy of Geology, was jesting about a steam-powered sex machine. But leaving aside his sex-infused musings, Hutton could see that steam-power had enormous potential – Watt’s machine could lift massive weights and its enormous strength was all down to one thing: heat. Perhaps heat was the source of the force that could lift mountains. Perhaps the centre of our Earth contained a mighty heat engine. In his 1788 treatise, Hutton waxes lyrical about steam as a planetary power…

‘The end of nature in placing an internal fire or power of heat, and a force of irresistible expansion, in the body of the Earth, is to consolidate the sediment at the bottom of the sea, and to form thereof a mass or permanent land above the level of the ocean, for the purpose of maintaining plants and animals.’

Hutton’s internal heat – and the power it conveyed to the surface – provided the planet’s counterweight to the destructive actions of erosion. Sediment carried to the sea gets laid down, compressed and heated up. Molten magma deep underground rises back to the surface to create new rock, buckling and lifting the layers above to create hills and mountains. Mountains which once again get washed into the oceans. And the whole cycle starts again.

It was, he realised, an ordered, perpetual recycling system that was akin to the predictable movements in the heavens above…

For having, in the natural history of this earth, seen a succession of worlds , we may from this conclude that there is a system in nature; in the manner as, from seeing revolutions in the planets, that there is a system by which they are intended to continue these revolutions.’

The notion of Earth as a ‘system’ is one of Hutton’s great contributions to scientific thought, and one that no doubt stemmed directly from his early fascination with blood coursing around the human body. Looking at the planet from the perspective of physiology rather than mechanics, gave Hutton a further twist…

‘But is this world to be considered merely as a machine, to last longer than its parts retain their present position, their proper forms and qualities? Or may it not be considered an organised body? Such as has a constitution in which the necessary decay of the machine is naturally repaired, in the exertion of those productive powers by which it had been formed.’

Hutton’s Earth was not simply a mechanical contraption driven by heat expansion, but rather an self-correcting system of thresholds and feedbacks that regulated its own internal functioning despite external disturbance. In essence, that depiction is identical to the very modern notion of Gaia, put forward in the late 1970s by the British inventor and environmental thinker James Lovelock. Lovelock’s Gaia is that the living organisms of the Earth and the soil and rocks on which they act form a system that behaves as a single living entity. Many geoscientists recoil from the mythological overtones and perceived New Age pseudo-science of Gaia as Earth Mother, and stop short of its inference that the planet may be better conceived as a sentient superorganism. Nevertheless, modern geology has assimilated Gaia’s core ideas of inter-connectedness and given them its own name: Earth system science.

Earth System Science may not be a name that stirs the imagination or the passion about our natural world, but its tenets lie at the heart of how scientists look at the planet. Spheres that were long regarded as discrete entities, and studied as such – the solid earth (lithosphere), the icy extremities (cryosphere), the atmosphere, the hydrosphere and the biosphere – now demand combined investigation. Across the globe, natural scientists are coagulating into sprawling interdisciplinary agglomerations of biologists, chemists, geologists, physicists, and other specialists. Collectively, it is a return to the polymath times of the early natural philosophers like Hutton.

Back in the 1780s, Hutton’s recognition that the timeless nature of the constant cycling between land, air and sea meant that the whole question of ‘time’ became relative and rather abstract. The planet operated on ‘deep time’ – unfathomably long periods of slow, incremental change. It gave him his most famous final words, the parting shot of his ‘Theory of the Earth’

The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.’

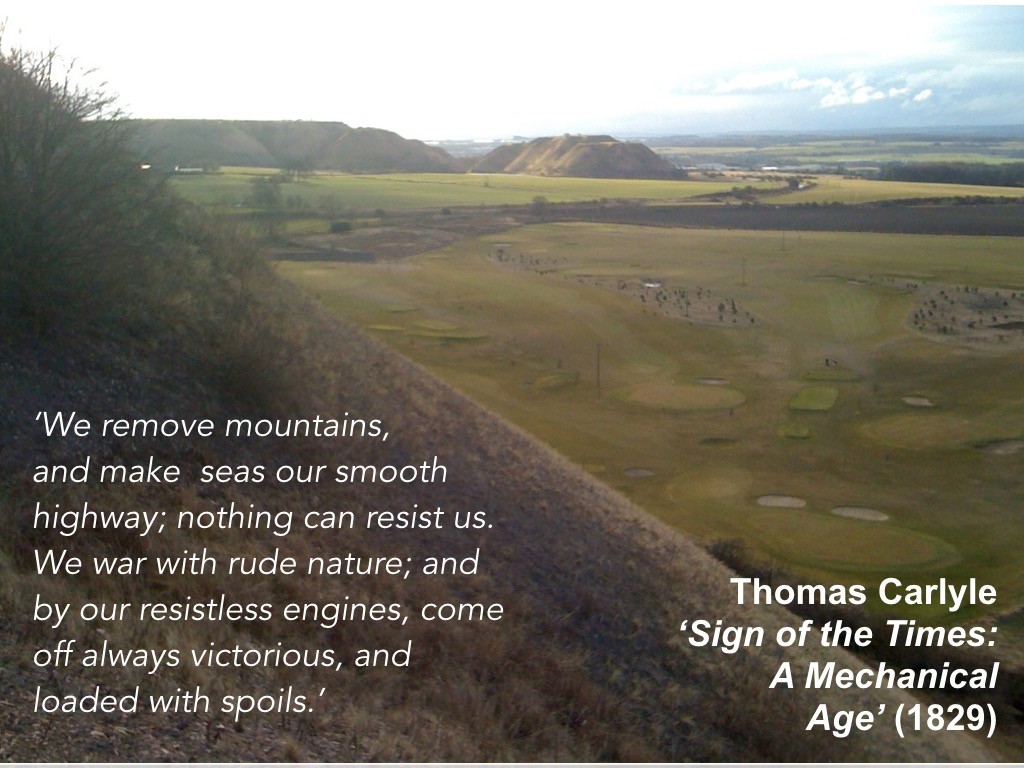

But even as Hutton penned those final words, his notion of a balanced, perpetual world was unravelling. The tightrope act between the constructive and destructive forces that maintained our habitable world had been disrupted. The root cause was James Watt and his steam engine, which ushered in, with quickening pace, the Industrial revolution. The spirit of that new industrial age was later captured by the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle:

The rampant industrialisation of the 19th century not only gave economic wealth to the nations of America and western Europe, but it launched a new geological era: the Anthropocene. The geological era of humanity. A period when the slow actions of the planet were outpaced and outcompeted by the transformative actions of humans, their machines and their pollution. Today, the concept of the Anthropocene age dominates the thinking of many environmental writers, notably the cultural historian Thomas Berry in his 1999 book The Great Work…

‘…we are at the present time participating in an unparalleled change in the human-Earth situation. The planet that ruled itself directly over these past millennia is now determining its future largely through human decision…’

And so we arrive at the critical need to have a Sustainable Earth Institute (SEI). In fact, those three words are crucial, because they each reflect different facets of the problem.

‘Earth’ grapples with the history of the planet’s turbulent past, unraveled through a rocky archive that reveals both its capacity for slow or dramatic change and its intrinsic thresholds of operation. It tries to understand how this diverse world around us came to be, and how its natural actions limit and threaten us.

‘Sustainable’ compels us to better understand that delicate balancing act between Society and Nature. It challenges us to maintain the resilience of one without compromising the integrity of the other. It is concerned with establishing a health check for our environment, monitoring its well-being and detecting change. But it’s also about reassessing and reimagining what individuals, communities and societies need from the natural world.

‘Institute’ addresses that new human decision-making about the planet. It is concerned with how we institute societal change by better understanding of the political, economic, social and cultural levers that motivate governments, corporations, communities and citizens. It rests on engagement with the human sciences, the business sector and the creative arts, inviting inquiry from artists and writers, political scientists and economists, psychologists and sociologists, and practitioners of all types.

In its journey ‘towards a sustainable Earth’, SEI will extend James Hutton’s planetary physiology into a broader consideration of the long-term vital functioning of the human planet. Yet, with the looming spectre of global climate change, Hutton’s opening words have more urgency today than they did at the dawn of our modern age…

‘This globe of the earth is a habitable world, and on its fitness for this purpose, our sense of wisdom in its formation must depend’

Iain Stewart

Director of the Sustainable Earth Institute and Professor of Geosciences Communication

Isn’t amazing how a cartoonist or a comedian’s few words can sum up a situation so succinctly! Carlin’s quote is perfect. Excellent “brief history of …” Ian